Write the Vision: Quakers, Zines and Participatory Culture

This is a synchroblog written for Quaker Voluntary Service, of which I am a board member. The theme is “Quakers and new media.” (Twitter Link #qvssynchroblog)

“Write the vision; make it plain on tablets, so that a runner may read it. For there is still a vision for the appointed time; it speaks of the end, and does not lie. If it seems to tarry, wait for it; it will surely come, it will not delay.” (Habakkuk 2:2–3 NRSV)

Early Publishers of Truth

Early Quakers called themselves, among other things, “Publishers of Truth.” They published truth with a missionary fervor, writing in order that a new world would be given forth from their written, as well as spoken, words. As I read early Friends, I see their publishing being very much related to how they understood the mission of the church to be, at its heart, participatory. As we think about who and what are the publishers of truth today – and if there is even such a thing left – I can’t help but suggest that any form of publishing that is not at its core participatory, inclusive and prophetic in nature is not rooted in the identity of these “Publishers of Truth.”

Just by way of background, these Publishers of Truth were an almost unstoppable force. Consider what Quaker historian, Elbert Russell, says in his “The History of Quakerism” (1979),

In spite of some arrests for owning, circulating or selling Quaker publications, and in a few cases the seizure of destruction of offending presses, there was a large output of printed matter. In the seven decades after 1653 there were 440 Quaker writers, who published 2,678 separate publications, varying from a single page tract to folios of nearly a thousand pages (79).

Russell goes on to explain how censorship worked back then, first oversight was given by George Fox, then it moved to a designated meeting of elders. The nature of the writing was often publicly articulating their beliefs, writing epistles to other meetings, creating pamphlets and responding to attacks from their detractors (80). There are others who can track the history of publication far better than me, but for much of Quaker history Friends have kept a steady hand on the printing press and they left us something to learn from and build on today. It was an essential thread to who the early Friends were.

What are some of the things we can learn from these first publishers?

First, it was many voiced. Both men and women were involved in publishing and these early opportunities created the opportunity to gain a voice for those on the margins within a largely unequal society.

Second, it challenged sanctioned readings and interpretations. Any time a text or work of art is remixed there is almost always someone up in arms over it, and yet Quakers constantly remixed biblical texts, and challenged sanctioned readings and interpretations of the church. In other words, their Publishing of Truth was often perceived as an act of publishing untruth by those whose beliefs and structures were challenged by what was written about. Third, and very much connected to this previous point, while there was internal censorship, Quakers exploited the lack of copy-write and censorship of the press (Russell, 79).

Fourth, they were engaged in public dialogue, debate and concern towards the well-being of society – consider for example, John Bellars’s “Proposals for Raising a College of Industry of All Useful Trades and Husbandry (1695)” which outlines the possibility of responding to the crippling poverty of his time.

DIY, Zines and Participatory Culture

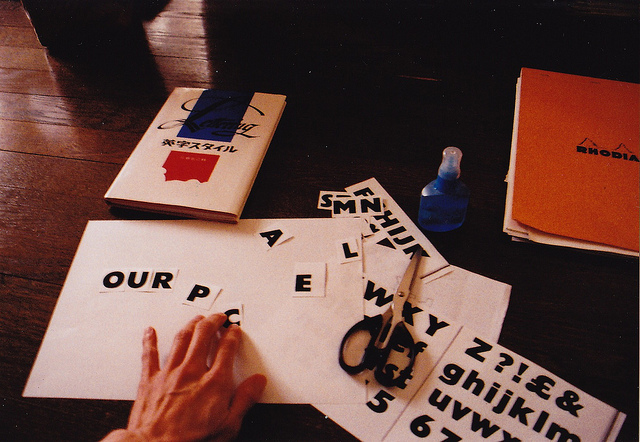

Underneath all of this is a DIY ethic, or even a kind of fan subculture that early Friends were working to create through their publications. Like the DIY ethic of the 70s Punk Rock scene, and other early fanzines and fan-fiction, Friends were not simply anti-establishment, or even anti-organized religion, they were attempting to build a many-voiced culture by attempting to create the kind of church, and world, they wanted to be a part of. All of their pamphlets, tracts, and other publications are just seventeenth century versions of the kind of DIY fanzines of the 70s, 80s, and 90s. One of the underlying principles of participatory culture is if you want to be a part of something that does not yet exist take it upon yourself to “produce what you want to consume.”

Looking at the “Publishers of Truth” from within this participatory framework allows us to see publication as an act of producing rather than consuming. This kind of publishing is many-voiced – or inclusive, it is prophetic insofar as it “remixes” original texts, ideas, artwork, challenging sanctioned ideas while putting forth new ones, and it is participatory because those who write often write to be authentic to their own experiences.

In other words, from within this framework we see that publication is a way to create culture, to put forward ideas and generate new thoughts, debates, as well as to comfort, guide and build connections with others. If publication is about this kind of “producing of that which we want to be a part of” than we can without a doubt find plenty of places where this kind of publishing is still happening within the Quaker world.

The End of Publishers of Truth Today?

Before moving on, I want to suggest some questions that might guide further reflection about being “Publishers of Truth” today. When we look around it is hard not to see what looks like a decimated world of Quaker publishing. With the exception of projects such as Friends Journal, QuakerSpeak.org, QuakerQuaker.org and a few others, I see very little new happening in when it comes to Quaker publishing – at least within American Quakerism.

However, I see a distinction between the Quaker publishing industry of today and the DIY pamphleteers of yesterday. Early Friends wrote because they had something to say, the had truth that needed publishing, and they did this without setting up non-profits, boards and raising thousands or millions of dollars to do it. In fact, as far as I know little, if any money, was made on these early publications. Today’s Quaker bloggers are much closer to the early Publishers of truth than our institutional publishing companies run by Friends today. It’s one thing to have a bottom-line to meet, staff to pay, and a reputation to uphold, it’s quite another thing to write as a prophetic act, to write because one is compelled to write, to publish because to not publish is to leave the ground fallow and let the seeds of new life become stale.

I hope you don’t hear me saying that I am opposed to what we might call “denominational presses,” because I am not. I think they have a place and are necessary. In fact, we could use a couple really strong denominational presses that service the whole of the Quaker tradition today. However, I just because there is a press or publication run by Friends does not necessarily mean it carries these participatory, DIY features that I am trying to draw out here.

Let’s consider some of the challenges Quakers face when it comes to publishing, especially as it pertains to our more organizational models.

First, there is a crisis of identity. Early Friends were able to write and articulate a theology because they had a theology to articulate. They had clear boundaries and convictions and they had detractors who constantly debated them. Whether you find yourself on the right or the left end of the Quaker family tree, we have for the most part lost this sense of tradition and identity. Having a place to stand gives one a place from which to speak and write. Having a transformative encounter with God, and being formed by our tradition is a part of that identity formation. What is this place for Friends today?

Second, parochialism. If early Publishers of Truth were public ministers and public theologians, we, by and large, have gotten lost in our private language games, internal debates, and have lost connection to the larger debates that are taking place in our culture (with maybe the exception of politics). Have we become too parochial for people to pay us any mind? If I were an outsider would I even know where to begin, or know how to engage the internal debates of the Quaker tradition? What would it take for us to begin showing up at other conversations, challenging theology and interpretations that continue to oppress others, finding ways to get caught in the fray, learning from what others have to teach us?

Third, an inability to move towards risk. It is my perception that much of what is now Quaker publishing is working from a reactive, or market-driven, model of publication. Where can we make money? Who is buying what? This sold so let’s publish more of that. This makes us beholden to certain topics, themes, or particular constituencies that can hamstring us later if we want to change directions, challenge the status quo, or bring up difficult conversations. What can we learn from the DIY ethic and fanzines that can help us re-establish a participatory, productive, approach to publishing? We don’t publish to the market, we publish because this is what is most true, most authentic, most alive and what needs to be written.

A Convergent Model of Publishing

In the Hebrew bible God tells the prophet Habakkuk to “Write the vision; make it plain on tablets, so that a runner may read it. For there is still a vision for the appointed time..” I believe this is exactly what Friends need to do if we hope to not only engage in publishing truth, but in the renewal of our tradition. There is a vision to be written and when we wait for it, God gives it.

I would like to see existing and new Quaker organizations move more towards what I would call “a convergent model” of publication. Drawing on the rich and vibrant voices within our various streams Quaker publications can model what it looks like to be many-voiced, embracing and building up the beloved community. Recently, Friends Journal has impressed me with how it is working to be many-voiced, both in terms of who writes and the viewpoints and questions shared there. There is more work to be done, and in DIY models of publishing the threshold and censorship is lower, the point is to get voices out there and lift up authentic experiences.

A convergent model of publishing will also encourage grassroots connections and participation. One of the things I love about “Quaker fan network” QuakerQuaker and the vast Quaker blogosphere is that there is a shared vision of encouraging Friends to write and helping to amplify voices. From sharing and cross-posting other Friends’ writings on Twitter and Facebook, to guest blogging, to hosting “how to blog” workshops at Yearly Meetings, I see the Quaker blogosphere as a rich example of participatory culture. I also see it as a vehicle to creating real connections and relationships. I am constantly surprised by the people I meet as I travel and friendship that are created through these online interactions.

Finally, I am convinced convergent publishing must move in the direction of remix. Remix in Hip-Hop culture is a way to pay homage to the past by sampling a particular beat, instrument or lyric, and then adding your own new ideas and layers to it. I find a good remix to be prophetic in the way it seeks to create something new out of something old. And this is what I think Friends need to be do within the Quaker tradition. Consider, for example, Freedom Friends Faith and Practice. It is one such example of a Quaker remix. They borrow from the programmed and unprogrammed traditions, from progressive and evangelical viewpoints and in the process they have created something fresh and new within the Quaker world. We need new ideas, new questions, creative engagement, clear vision, people who are not afraid to take risks, ask hard questions, and push the edges. It’s important to remember that Fox, Nayler, Fell and others were not always popular when they “wrote the vision.” I think we also need people who are able to dialogue with those on the outside the Quaker tradition. People who are curious and interested in what is happening outside the hedge. To Remix is to not only be creative, challenge the status quo, and question sanctioned interpretations, it is to be familiar with the many ideas – or “samples” – that are available to draw on from our culture.

Conclusion

Early Publishers of Truth were inspiring because of their DIY ethic and missionary fervor they brought to publishing. I wholeheartedly believe their publications not only helped to bring about change in the rest of Christianity, it is what built momentum and established the Quaker movement as a viable and lively thread within the Christian tradition. Publishing from a participatory perspective is about writing a vision: writing as a means of birthing something new, writing to generate the kind of world or culture you want to be a part of and in doing so create a space for others to participate with you in that vision. I am hopeful that as Friends encounter the Spirit and are faithful to what we are called to, we will continue to be given a vision to write, and a truth to publish, and that will indeed make us a peculiar people.

See other’s posts in this synchroblog: (Twitter Link #qvssynchroblog)

- Martin Kelley – Preaching our lives over the interwebs

- AJ Mendoza – Queer Quaker

- Jon Watts – Can Self-Promotion Be Spirit-Led?

Ideas for this post are drawn from my dissertation and upcoming book “A Convergent Model of Hope: Remixing the Quaker Tradition in a Participatory Culture.”