When We Need Bread (John 6)

This past weekend, I had the pleasure of preaching for College Park Baptist just up the street on chapter 6 of the Gospel of John.

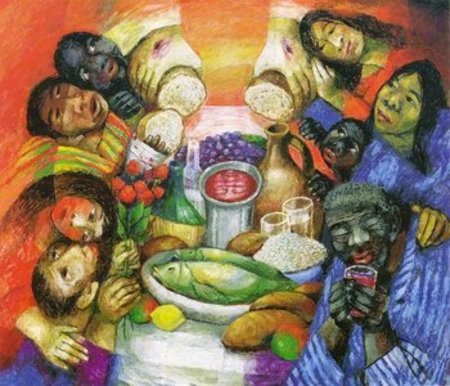

“I am the bread of life.”

-Jesus

At Guilford College where I work as a staff member and part-time faculty, I have been co-teaching teaching a class called Food and Faith for the past couple of years with “B.T.,” an incredible friend and colleague.

In the class we explore the intersection between food and faith: we eat food, we talk about our personal and collective histories of food, we learn how different religions interact with food, and the ways the global empires within which we are situated, grow, use, profit from, and control food and the land and water it grows from.

I have learned through this class that food is more than just fuel that runs our fast-paced lives marked by long lines at our favorite fast food restraunts, Trader Joe’s pre-made dinners (of which I am grateful for), the invention of the mircowave, instapots, and airfryers, keurigs (don’t get me started!) and of course – in my opinion the monstrosity of the new genre of food science invented: energy drinks like Monster, Rockstar, C4, and the G FUEL energy drinks that comes in two flavors: “Black Ooze” and the “Red Ooze.”

Food is more than fuel. It is more than something to simply hand out and quickly consume.

Food is an entry point, a lens into every aspect of our lives.

Food helps us explore community, faith and family, climate change, racism, class, economy, imperialism, our relationship to our bodies, our relationship to one another, our relationship to God, to the land, to workers who labor for the food, how make the food, and those who sit down together creating a family around the bread we bread.

As Danny Rojas from the show Ted Lasso might shout: Food is life!

Jesus is the bread of life

When I read this passage in John 6, where Jesus refers to himself as food by saying, “I am the bread of life,” I cannot help but hear an invitation to see bread as something more universal, something more powerful than just fuel to be consumed. It is a gateway into seeing how we understand and live in the world.

Bread is a universal metaphor for that which we all need to live.

Bread is life.

Just a few verses before in this same chapter (John 6) is a story you are all familiar with: the feeding of the 5,000.

What does Jesus feed the masses with?

Fresh Fish and … bread.

Here Jesus is found near the sea of Galilee on the side of a large hill with a crowd gathered round. He had been teaching the people for some time, it was almost Passover, so it is getting late and Phillip sees all the people, and rightfully so is probably hungry himself, and wants to know – when we can stop with the teaching and start with the eating.

What do we do when we there is not enough bread to go around?

Pause right here for a second and imagine this crowd, which is bigger than a crowd. In the great it is “ὄχλος πολύς.” Literally “a great army” this phrase is later translated in Revelation 7 as “the multitude.” A translation I prefer because it tells us something about this crowd.

Wes Howard-Brook (John’s Gospel and the Renewal of the Church) says that this crowd is made up of those who are:

- The poor and dispossessed.

- Galilean country-side folks who were, generally speaking, not just poor but, leary of establishment figures given their own very low status within the Roman empire and the religious institutions of their time.

- And disaffected peasants, who I hope you have already noted, are not at the official passover ceremonies but outside on a hilltop with some poor, Rogue Rabbi who is clearly standing outside organized religious authority.

This is why one chapter later this multitude are called “cursed” by the pharisees for their ignorance of the sanctioned interpretations of the Torah.

In other words, here we find Jesus, a poor teacher and prophet, on a hillside organizing other poor people (we all know how that generally goes, don’t we?).

We come back to this question of feeding the 5,000 and Jesus responds with another question:

“Where are we to buy bread for these people to eat.”

Options of Response

Let’s consider the options for response to this question: what do we do when we need bread:

- We take the individualized approach and send them on their way home to fend for themselves. Have we ever seen this modeled in our families, communities, or country?

“Look, you’re on your own. It’s not our problem that you didn’t think ahead and pack something.”

“It’s not our problem that you don’t have enough to eat to begin with. You’re probably lazy or have done something to deserve it.”

“You needing bread is not our problem.”

Does that sound familiar?

- We takes Phillip’s idea and we try to figure out how to pay for everyone’s meals. Phillip goes right for the charity model — how much money is it gonna cost for us to pay for everyone. It is our responsibility to fix it for them. The charity model of response to poverty maintains distance between us and them and creates a power differential that keeps people in poverty while not disrupting the systems that created and perpetuate the problem. It is often a quicker, easier solution in the short term to just throw some money at it, but despite billions of dollars flowing through the non-profit industrial complex, people remain hungry and face dramatically higher rates of illness and mortality due to lack of nutrition.

- A third option is to read the feeding of the 5,000 the way we normally do, something spiritualized and therefore out of our hands. We often read this story as a miracle that only Jesus can do; this is a problem only Jesus can fix. In this reading, the disciples are more spectators rather than participants, stepping back in hopes that Jesus can resolve the issue. We hear this spiritualization of concrete needs when people use phrases like “you are in our thoughts and prayers are with you.”

To the nearly 41 million living below the poverty line and the 140 million Americans who are poor or low-income we hear many who confession Christian faith to pass this off with “our thoughts and prayers” are with you.

“Our thoughts and prayers” when we see children go without food and four and 10 children in the US spend at least one year in poverty.

“Our thoughts and prayers,” when we experience gun violence in schools and community centers.

“Our thoughts and prayers,” in the face of ongoing police brutality.

“Our thoughts and prayers,” when learning of violence against people who are Lesbian, Gay, Bi-Sexual, Transgender, and Queer.

Spiritualization happens when we hear, “it’s all gonna burn anyway, why care for the land and animals and so on?”

“Thoughts and prayers” rests on a spiritualized reading not only of this story but of all of Jesus’ life. He is the the only one who can live out these kinds of ethics and calling. But all this really is is an abdication of all responsibility in the face of grave injustices.

Can you see how these three (Individual, Charity, and Spiritualized approaches) are all ways in which we as a society living in an age of empire tend to respond of what do we do when the poor need bread?

- There is a fourth option is a longer term plan that is rooted in the participation and agency of everyone and seeks to build new systems of sharing and distribution among all in need. This option is about inhabiting a different world, with an re-shaped imagination, finding oneself within an alternative community that resists the influence and business-as-usual of empire. In our day and age we might call this story an example of a project of survival. Folks are fed and they are given the necessary analysis to organize as a community and resist empire and its beastly economics (that’s I think these teachings surrounding this event are about).

I am choosing the name “projects of survival” here very carefully.

The phrase “projects of survival” originates, as you probably know, from the Black Panthers and names a project that is both about meeting concrete, immediate needs, while educating and organizing the poor and oppressed in such a way that those needs are no longer constantly in threat.

This comes out of the Black Panther’s own Breakfast Program – a free breakfast program that fed tens of thousands of children and created a basis for educating on the failure of Johnson’s War on Poverty and how a country so wealthy was using that wealth to harm poor people both in the US and around the globe (Sandweiss-Back).

Examples of more contemporary Projects of Survival are:

- Put People First PA – Recently taking on the state’s closure of hospitals in poor and rural communities leaving some communities with 2 hour drives to the get to the nearest hospital.

- National Union of the Homeless – The homeless organizing and running their own shelters, seeking to bring an end to homelessness. “Homeless not helpless”

- Fight for 15 – NC Raise Up – Not only are they fighting for a better basic minimum wage but they started Fed-Up in order to organize food drives for fast food workers who are going hungry while working 2-3 jobs trying to make ends meet.

Noam Sandwiess-Back, writing for the Kairos Center, says that:

“Projects of survival do many things:

- they meet the needs of people who can then come into new political consciousness;

- they encourage and secure leaders who have a sense of their own agency and political clarity;

- they connect to political programs that rely on many different tactics and strategies;

- they expose the larger society to the moral failures and contradictions of governing [and I’ll add religious] systems;

- and they make demands and claims on the power of the state.”

What do you think about the feeding of the 5,000 in this view?

Read over these again. I think Jesus’ action here fits all of this.

Jesus’ goal here, and throughout the Gospels, is both to meet basic needs while also educating and organizing the poor in his time so that truly another world might be possible.

When Jesus gives bread and then says his way is itself the “bread of life” we get a glimpse at his strategy as a poor person organizing other poor people.

Jesus being the bread of life is both the concrete need of food and the political, theological education necessary to resist empire and follow God no matter the cost.

Bread enough for everyone is a key part of Jesus projects of survival.

We know this because of what is said in John 6 but also the multiple feeding stories. The prayer he taught his disciples to live by asking for bread enough for today, and the broken body as bread that we remember today.

Jesus demonstrates to the multitude that projects of survival are not only an economy based on bread enough for everyone, but what they are capable of together as an alternative Eucharistic community no matter how poor and “cursed” they are.

A community grounded in meeting concrete needs, with the theological and political analysis needed to challenge the powers and principalities out of alignment with God’s purposes.

Jesus is the bread of life.

To eat that bread, to commune with Christ who is present in our midst with those at this table is to enter into a different way of being human, a different way of being in community together, a different way of relating to ourselves and to God.

Living into this means we will, as Wes Howard-Brook puts it, “the social consequences of participation in the Eucharistic community amid imperial supervision.”

What do we do when there is need bread?

When those in our community are literally starving, being evicted from their homes, cannot pay their utilities, being brutalized. Do their needs and voices go unheard? Do we expect them to take care of it themselves? Do we hope a charity somewhere is dealing with the problem. Do we spiritualize it and hope Jesus will solve the problem? Or are we finding ways to create, join, and support projects of survival rooted in Jesus’ economy of enough.

As we take all that we have learned during this pandemic and apply it to an (almost) post-pandemic world – where can College Park be living into this alternative economy? What projects of survival are you being led to engage with no matter the social consequences? What does it mean to this community to embrace the bread of life as a way for all of life?

Queries:

- When you look at bread as a doorway into our individual and collective lives what do you see?

- What do we do when we need, or see others in need of, bread?

- What projects of survival are you familiar with?

Benediction:

And some are beginning to remember to decide to hold hands anyway

(And some never stopped remembering to hold hands anyway)

And some are bearing witness while others give away their bread

We will be the ones, with poetry in our hearts

Who rhyme love with love with love with love with love with love with love