As I continue to think about John Howard Yoder’s sexual misconduct and the reality that within his theology there is either implicit or explicit justification for this kind of behavior, I am concerned that my own theology is not only susceptible to this, but has already been impacted.

- How can I become more aware of my own blind spots?

- In what ways am actively participating and benefiting from patriarchy within my family, my ministry, my friendships, and my teaching?

- How am I allowing myself to be held accountable to other men and women?

- Am I really sharing power or am I finding ways to put on appearances while getting my own way?

If I follow out the idea of “Biography as Theology,” then I really want to know, and reflect on, what it is that I could be building instead.

I realize that challenge lies ahead.

I cannot take coverage as a “progressive” white male from this.

I can no longer take coverage in what we Quakers call the “peace testimony.”

For that matter, I cannot take coverage in calling myself a Quaker, either.

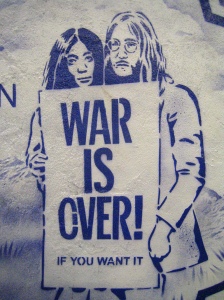

I think the peace testimony actually covers up a lot of problems within our peace churches. It is easy to call oneself a Quaker, a Mennonite, a radical, an anarchist, whatever your handle, and say we adhere to peace. But what does that really mean? That we preach sermons on peace? Or go to protests and hold signs? That we have anti-war stickers on our $1000 computers made in terrible working conditions or on expensive cars made from rare materials stolen from mother earth and by the hands of those who we disregard? That we continue to talk about how Bush was wrong, or all the problems with wars long since past?

In reality, I am more interested in the question: is talking about peace really helpful any more to anyone other than ourselves? We often use “peace” as code language. Under the name of peace we do a whole lot of violence, we tell a whole lot of people we devalue them and the choices or beliefs that they hold. Peace often operates as a cover to hide from the fact that we are in fact not interested at all in the kind of peace that would cost us our positions, our power, our own sense of being right, and our own group belonging.

In what way has our understanding of peace meant to do away with violence actually preserved a war between “us and them,” preserved violence upon others who are different from ourselves?

The more I dwell on this, the more I realize that I am in need of confession. That I have been wrong about the peace testimony. I have been wrong in calling myself a pacifist. Just as much as I have wanted to believe in peace as a way to protect others, I have used it to protect myself from others who might critique my use of power. I have been brazen and arrogant in thinking that somehow I understand the complexities of other’s lives, while at the same time not living a life that reflects the deep love of God.

If we use others to our own end, then we have no right calling ourselves practitioners of nonviolence. If we think that blowing the trumpet horn of peace somehow makes us more right or righteous, or justifies our own “marginalization” and shrinking numbers, then we have duped ourselves and bought into a lie sold by the devil himself.

Any theology that protects our position, that doesn’t expose us to critique and challenge, is violent. We – and yes I – have used the peace testimony against others. We have turned it out like a shield, hoping that it would somehow shelter us from assault, and protect us from the critique we desperately need to hear.

Yoder’s fall is symptomatic of a deeper problem within our current understanding of “peace.” What I am trying to say here is that what often gets labelled as “peace” is nothing more than a middle-class, white supremacist grasping at straws, used to justify our existence, our abuses of power, our disgruntled attitudes, and our inability to play well with others under a noble-sounding cause. How many non-whites do you know who think about, talk about and obsesses over peace the way we do? If we want to have a peace forum, let’s invite a diversity of voices, experiences, classes, and thought around the subject. It’s time to shut down the echo chamber.

This whole thing is not only wrong-headed but just down right dangerous. The fact that many have been hurt, excluded and often attacked by those who claim to be pacifist is an indication that the peace movement is broken, dead, or has lost its integrity.

The world doesn’t need more pacifists, the world doesn’t need more people adhering to the peace testimony, and God knows, the world doesn’t need more stickers claiming that “war is not the answer” – full disclosure, I have one of these stickers on my vehicle too. The world needs people committed to loving their neighbors and loving their enemies. This is a far more challenging call. This has a much sharper prophetic edge. Jesus never suggests his followers become “pacifists.” Jesus embodied the way of nonviolence, a way that is non-abusive, a way that holds the tension of neighbor and enemy, a way that does not call profane what God has called sacred, nor does it create an us vs. them. In other words, it’s nothing like most of our churches and meetings today. Instead, Jesus taught us to see the God of love as the one who calls us all together into a new humanity. Jesus said those who live by the sword die by the sword, which I take as his way of saying that absolute power will kill you no matter what your weapon of choice is – a sharp metal object or beautifully written theology.

We need less violence in this world. We need a lot less male theologians and pastors abusing others. We can start from a place of recognizing that we are all guilty of violence, even and especially when we claim to be practicing peace.

How about we take a break from sermons on peace? How about we take our flags of peace down? How about we stop talking about peace for a while and lay this whole thing to rest? Saying “peace” is cheap, building a community where people are honored for who they are and are welcomed regardless of where they stand on “the issues” would be a far better place to start.

Maybe in letting the thing die something new will be born in its place, something that is truly reflective of the beloved community where brothers and sisters are in mutual participation, where many voices are presented, and where we no longer avoid the hard work of becoming fully human.

God Help Us.

Edited: I want to identify that I was greatly helped in these thoughts by Jamie Pitts and Malinda Berry, two people whose own thinking and work in the peace church world is exemplary.

Flickr image credits – link