The Problem with (Quaker) Values

Originally published on my “Resisting Empire, Remixing Faith” Newsletter.

As you may have seen, there is another flair up in the news about another Quaker school being caught in a debate around Quaker values. This time it is Brooklyn Friends School when the head of school sought to decertify the newly formed faculty/staff union. It’s already one thing to try and break up a union, it’s a whole extra thing to justify it by citing “Quaker values.”

The presence of a union violated the school’s Quaker character, she wrote in two August 14 notes to teachers and families. “If we are to fully practice our Quaker values of respecting others and celebrating every individual’s inner light while compassionately responding to existing needs,” she said, “we must be legally free to do so.”

This comes after Sidwell Friends, one of the most – if not the most – prestigious Quaker schools in the country, earlier in the year cited Quaker Values as their justification for why they did not need to return stimulus money they received from the government.

…The board of Sidwell Friends School, the private, hyper-selective alma mater of the Obama and Clinton children in Washington, D.C., argued that it should keep the $5 million it had received for a different reason: “The Board determined that accepting the loan was appropriate and fully consistent with its fiduciary responsibilities, as well as our Quaker values.” What do Quaker values have to do with taking out a loan intended for struggling small businesses?

As you can see, and as Adam Harris writes in his Atlantic piece, “Quaker values can be remarkably flexible.”

I could go on with examples and trust me when I say the examples are many, but these two high-profile cases are enough to build on.

Instead of trying to decide whether union-busting or wealth hoarding fit into “Quaker values” or not which tends to be the focus of these debates (you can probably guess my perspectives on each), I want to question the whole enterprise and call for a moratorium on the use of “Quaker values.” The problem with Quaker Values is not adjudicating between who is and is not interpreting them properly. The problem is how and why they are being used in the first place.

The Secularization of Faith Traditions

I first came to the realization of the problem of Quaker values while working at Guilford College. Without a long historical backdrop, Guilford was founded by Quakers in 1837 and up until somewhat recently saw itself as a Quaker, and therefore religious institution. After that, a shift took place and it has become more and more secularized. Today, there is no common language about Guilford’s relationship to its Quaker tradition and it certainly doesn’t see itself as a religious school. You will hear some call it a “Quaker school” (I believe there are 5 Quaker staff and faculty left), plenty are uncomfortable with that, especially any religious connotations that may be associated with being “Quaker.” The line that seems most acceptable to most people is that the college has a “Quaker heritage.”

The discomfort and indecision around what it means to be Quaker signals a break in the narrative of the college’s identity and relationship to the tradition that birthed it. Let me be really clear to say we can read this “break” in a number of ways. I don’t think this should all be seen as a bad thing. I, for one, am glad for the change in as much as it means there was a shifting away from being “Quaker” where that is code for white, middle-class, educated, etc. In the US, Quakerism is predominately white. Guilford’s student body is close to 40% students of color. Therefore, if we understand this breakthrough the emergent diversity and pluralism in staff, faculty, and students then I see this as a positive move. This shift also signals a move away from a “birthright” to a “convincement” culture, in that you can no longer assume knowledge, experience, or common religious/familial background experiences (not that you ever should but this is what happens in birthright culture). I believe that both of these are positive moves in institutions.

But we can read this in another way and that is about the ability for Quakers and the Quaker tradition to adapt religiously to changing needs, experiences, and community. The secularization of the college and institutions like it is a way of throwing up our collective hands and saying that we are unable or unwilling to allow our religious tradition to adapt to the shifting cultural contexts. I see this trend also in Quaker meetings and churches that are also following the path of secularization. In my opinion, Friends are guilty of allowing their communities to become secularized by offering lowest common denominator explanations and teachings of the tradition rather than addressing shifts in ways that are more meaningful, robust, and truly apprentice people to its ethics and tradition.

Without needing to know the specific histories of Brooklyn Friends, Sidwell Friends, and others, “Quaker values” is a sign of the secularization of Quaker institutions.

Jennifer Kavanagh says:

“This concept of testimony or testimonies is a key aspect of the Quaker way. To call testimonies ‘values’ is to secularise what is a spirit-based connection.”

Even with the positive intention that I believe is behind it: I see the move to Quaker values as a defensive move, one that seeks to resuscitate Quakerism in the face of major decline of Quaker presence in faculty and leadership in Quaker organizations. “Values” signals a last-ditch effort to have some Quaker remnant left.

There are a few other issues with values I want to suggest before finishing:

One concern is the way in which values are being weaponized against one another.One only needs to read the two articles above to see how “values” have become a way of defending decisions and attacking others. This is not a concern with the values themselves (equality, justice, peace, simplicity, etc) but with how they get used. I’ve heard people in institutions like this refer to Quaker values as both “a sword and a shield.” Something you can attack others with and use to protect yourself against others. All parties from students, staff, faculty, and administrators can be guilty of this.

A second concern is that is generally no real onboarding in organizations that still operate out of a “birthright” mindset. Birthright culture in religious institutions assume people either are already in the know or will have to learn osmosis (they will need to prove to us they are interested enough in our tradition to make the effort). Therefore, you may hear someone say “we have this and that value,” but any deeper narrative and practice that can actualize those values are rarely ever made. To onboard people is to fully welcome and include people, to be willing to “hand over the keys” and trust that there will be a faithfulness to operating things whether or not the original visionaries are there.

Given a full and deep understanding of the values (that are actually attached to Quaker testimony, which is attached to early Friends’ practices and reading of the life of Jesus, which is attached to their understanding of the Sermon on the Mount) gives way more depth, narrowness to interpretation and practice, and a historical handle on what Friends mean by the value of “peace” for instance. But this historical depth is rarely taught probably because it gets “religious” really fast.

Third, as you can see the values are highly individualized. Given the pluralism of our educational and non-profit organizations, these values are in our modern world are highly individualized (it is hard to imagine how they could be otherwise). We are all coming from different traditions and backgrounds. I see pluralism in this sense as both inevitable and something to be celebrated. However, when I think about “simplicity” as a value, I am generally left to my own personal interpretation of what that means in institutions where there is no longer any standardization or common shared commitment to how to practice simplicity. Generally speaking, our values are highly personal and left up to each to decide. Perhaps my interpretation of simplicity is to never own a car and only ride bikes and public transit. Perhaps another’s idea of simplicity is to own a hybrid, whereas another’s idea is to buy any vehicle they like so long as it is within their means to do so. Who is right? And who gets to decide? How would you get a pluralistic community to agree and for how long could that be maintained?

Fourth, I see “Quaker values” functions similarly to the way “religious exemptions” functions for the Right. Religious exemption – at least the way it works in the States, is that it is a blanket “protection” against something that goes against a group’s beliefs/practices. Cynically speaking, it often plays out in American as a means of protecting people (often Christians) from things they don’t like, don’t want to do, without having to do the harder, deeper work of discernment and dealing with underlying discrimination, bias, etc. I see it as often functioning as a quick-fix for an underlying and unaddressed bias within the community. I think “Quaker values” work similarly for liberal/left communities.

Sarah Jones in The Intelligencer picked up on this thread as well:

That Brooklyn Friends is a Quaker school, citing religious freedom in its petition for decertification, further rigs the game in its favor. The NLRB ruled in June that it has no jurisdiction over the employees of Bethany College, a Lutheran school — a carveout that severely weakened the labor rights of workers at religious institutions.

Conservative Christians and right-to-work groups hailed the Bethany decision, which means that liberal Brooklyn Friends could soon have some uncomfortable company.

Finally, I believe that for all the reasons above “Quaker Values” are not robust enough to shape and form an alternative community that resists empire, capitalistic forces, racism, and truly allow for the creation of the beloved community. I am okay with keeping the values language if it is in concert with other more culturally powerful ways of shaping and guiding the community. My hope is that the internal work that needs to be done can be done in such a way that institutions and organizations would not need to have these values posted anywhere, it would just be obvious that this community practices nonviolence, stewardship, anti-racism, etc.

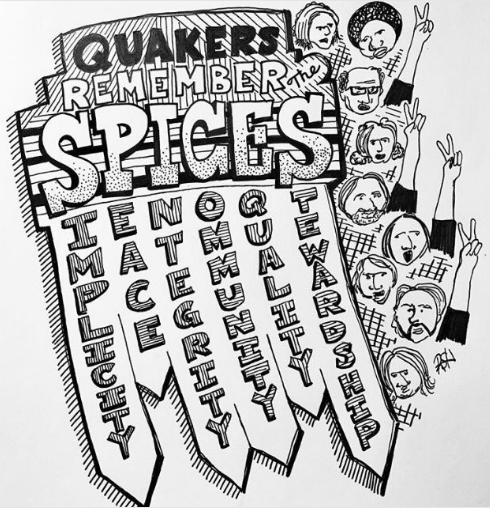

On their own “Quaker values” have become damaging both to the communities that use them and to the Quaker tradition. Therefore, might Quaker organizations issue a moratorium on the values (And S.P.I.C.E.S.!) until Friends can develop more robust practices and language to help move institutions and communities in a positive and generative direction? I believe that as long as values language allows Friends to limp along, these organizations will not be forced to rethink systems, practices, and processes that help to share moral communities. Without this, the last vestiges of the Quaker influence in these organizations will eventually fade.

Next week I will provide a few thoughts about ways forward: see part two here.

Query for Personal Reflection

- In your personal life, do you use the language of “values?” If so, how do you it and in what instances? What does it mean for you to have values and do you find that a helpful construct? If you don’t use this language, why not?

- Are you in an organization that uses the language of values? How does that play out in that environment? What do you see as the advantages and/or disadvantages to this?

To Move Beyond Quaker Values

“These value are important. They are not values that are automatically transferred without study, dialogue and experience. Opportunities to study Quakerism are needed in order to understand this particular heritage. Young people need exposure to Quaker process to understand both the vitality of Friends procedures and the patience required to solve personal and institutional problems through group deliberation. Leaders at all levels of Quaker organization need renewal in understanding enduring insights with fresh vision.” -Judith Weller Harvey (Founding Director of the Friends Center at Guilford College – 1982)

•◎•

In the previous issue of the newsletter, I called for a moratorium on values language within Quaker founded institutions or at least de-centering this language in favor of a more robust set of practices that can help shape these institutions. I believe this is needed because values language, for whatever good reasons they might have been adopted, they have run their course.*

My argument is that “values” are too simplistic, too rootless, and inadequate to guide communities in this time. They are too cheap in a time when “costly discipleship” is what is called for. Besides living through COVID19, we live in the midst of crumbling imperialism, crushing poverty, climate devastation like we have never seen, deeply divisive politics, ongoing and constant devaluing of African-Americans and people of color’s lives, all due to the distorted narrative of the religion of empire. “Simplistic, rootless, cheap” are not words that come to mind when I reflect on what it means to survive and resist in this time (link to my book Resisting Empire).

This is the reality (and future) we face.

This is what our children and our students are living through, growing up in, and will be graduating and going out into the world to change. Telling them we have the value of “stewardship” or “peace,” and putting it on a poster or a flag somewhere will do little to collectively stand up against the religion and liturgies of empire.

These secular values are not strong enough or robust enough to challenge the ideological machinations of empire, because they are themselves used, distorted, and weaponized by the religion of empire. If our communities are to resist and change our world for the better, we need a more potent and robust set of strategies and practices. When I say to resist I mean very deliberately communities that are non-violent, non-reactionary, not caught up in the rivalries, ploys, and plots of empire. To resist is to create alternative communities: what Revelation calls the Multitude and what we call in the Poor People’s Campaign a Fusion Coalition.

Here there are five suggestions for helping institutions with a Quaker heritage recover more than a flimsy link between past and present in order to help renew and revive these institutions in these times: Understand and interrogate history, discern new and appropriate business models and size, create robust onboarding procedures, recover and teach regularly core stories, develop and focus on core practices.

•◎•

Understand and Interrogate history

There is a history to be told about each institution and the compromises, adaptations, advances and retreats in its rich identity of being “Quaker.” There was a time before these institutions adopted values language. Was it that they had no values prior to this? How did the school function in a way that was more or less in line with the Quaker tradition prior to values language? What were the creation and adoption of values in response to?

I think one of the most interesting and challenging questions is: what does it mean to call a school or an organization “Quaker,” or “Mennonite,” or “Catholic?” Can institutions themselves be one of these things? If so how and why and when might that ever change or be called into question?

There is not time nor space here for that question, but how would you begin to answer this? And can institutions be more or less Quaker? If so, how? In what ways? Is the only option, the thinnest possible version of the tradition or is there another way?

This reminds me of the work of Baptist theologian James Wm. McClendon Jr. who writes about this from a Christian perspective but I believe the sentiment is useful beyond that tradition:

“Governments are not all as wicked as they can be, though all exercise power. Not all churches, nor all religious rites, are beneficent, and they are powers, too.”

“If we discard the mythical (and unbiblical) idea that all the powers “fell” in some timeless prehistoric catastrophe, then we are free to inquire, instead about the actual history of a particular power: the degree to which its politics and claims are functions of the creative and redemption power of God in Christ, and the degree to which these are corruptions of that power.”

At Guilford it was only since the early 2000s that this language was adopted, signaling the end of a long era of decline in the institution in terms of its adherence to Quaker identity. I’d posit that the adoption of values was a last-ditch effort to shore up some kind of Quaker(ish)ness in the college in the face of dramatic decline of Quaker students, staff, and faculty, and an overall assumed understanding and practice of the tradition.

Beyond knowing the history of the institution’s relationship to its tradition overtime, consider also race, class, and other social aspects of its history. Again, at Guilford, many of us have been working together to interrogate our history (and mythology) around race and the Underground Railroad in conjunction with our painfully slow integration of African and African-American students. Knowing this history and speaking truthfully about it challenges some of the Quaker myth embedded within our institutions and forces us to more meaningfully own up to the whole story. Slapping “values” on the wall is a very cheap way of dealing with major injustices and complex histories. Fighting over who holds the key to the values falls prey to the distorted mythology while not getting to the root of the issues.

Discern Appropriate Size and Business Structure

“Size alone, however, has seldom mattered to Friends. Instead, they have sought to be witnesses of truth.” -New England Yearly Meeting Faith and Practice

I’m struck by the lack of creativity in terms of business models I witness from many of these institutions. It seems that when looking at how Quaker-founded institutions work from a business perspective they are not much, if any, different from other private schools built on the growth treadmill. If the main goal – as it is for many businesses in late-stage capitalism – is growth-at-all-costs coupled with lowering expenses (especially labor expenses), then these institutions are not going to look any different. They will be private schools with a “Quaker” sheen.

Why not use the constraints within the tradition to explore and even create new models of business? What is the history of Quaker business practices? Is there any creative insight to draw on there? Adjusting to appropriate, smaller sizes that are more likely to be sustainable given the disruptive future we all face. Consider Triple B Corps, Co-Op models, employee owned businesses like Bob’s Red Mill, and even lessons from unique tech companies like Basecamp that aim to remain small and do what they do well creating a cap on how much they will do and take on. Why hasn’t (and couldn’t) a Quaker institution write a book like “It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work?” When I look at so many of Quaker institutions it is clear that business as usual is failing. It is time to allow the wisdom of the Quaker tradition and insights from alternative models of business to guide in this area.

In the past, Quakers seldom prioritized size and growth, especially when that got in the way of Truth and the needs of the community. We need to apprentice and hire leaders who believe the truth of this deep down in their bones, who are willing to get creative and rethink entire business models and reject the economic system that continues to disadvantage everyone except those at the very top.

Create Compelling Onboarding Procedures (with the purposes of fostering deep participation)

One of the challenges with many Quaker institutions from schools and non-profits, and even meetings and churches, is that when they operate under a model rooted in birthright culture they lack any kind of serious onboarding procedures that help bring people fully into the community.

Birthright culture works from the assumption that those in the community are family, have shared cultural experiences, and already know what is expected of them. This may have been largely true for Friends back when everyone in the meeting was born Quaker, however, Friends institutions today need to shift to a new model and outlook on what counts as Quaker.

Alternatively, convincement model expects that there will be new people interested in participating in these institutions – they will not have the pedigree or the right last names and cannot name their family’s legacies – and yet this kind of culture is ready and prepared to bring new people fully in as true (new) insiders. Convincement culture isn’t about trying to convert people to its ways, it is interested in making the resources of the tradition as widely available and accessible as possible so transformation can happen from within. This allows for each person – regardless of background, experience, and identity – the ability to take ownership over the tradition along with the rest of their community. This approach understands that new people have very little to no understanding of the tradition (starting out) but are, in most cases, are here because they want to be a part of this larger story and community.

One illustration that comes to mind is mixtapes. I think a lot of Quaker institutions today are like a 6th generation duplicate of a mixtape. The songs on the tape are faint, the labels and song titles are too faded to read, the story about the mixtape decontextualized from who originally made the tape, and why. A robust “onboarding experience,” or if you prefer apprenticeship program, would walk people back through those generations in order to get them as close to the original as possible so that they knew better what they themselves would be remixing in the future.

In many institutions with a Quaker background onboarding procedures (around the tradition) are more-often-than-not a 15-minute spot, or a morning staff retreat every few years – to talk about the “5 Quaker values” of the school. If all the tradition gets is a crash course it is no wonder that the institutions themselves on a crash course.

An onboarding process rooted in a convincement culture would be more like ongoing opportunities that help develop and invest in staff overtime, slowly inducting people into the tradition, believing that good practices, processes, and procedures rather than strong personalities and protecting legacies is the way to pass on tradition and help these institutions survive. It also makes for more equitable, more stable, and more participatory organizations because everyone knows what is expected and no one or two leaders run the show.

Core Stories and Core Practices

Finally, we come to core stories and core practices.

In order to build a robust culture, the ability for more moral reasoning, and deeper shared language that can help guide institutions through these challenging times, I suggest drawing on core stories and core practices as the key to what we do.

Core stories or narratives should be among the first things developed. Many of the schools and institutions that suffer from the challenges under discussion have really powerful and important stories in their history. Stories that go back to why and how the school or institution was founded. Challenges they have overcome along the way. Points in time when there were big decisions that impacted the community and how that was handled. Major failures and breakdowns in leadership.

When I say core stories, I do not mean retelling stories of hagiography: the over-simplified stories that reinforce the mythology and often (Quaker) Exceptionalism of a place. I mean the far more complex stories that arise from communities trying to be faithful, sometimes succeeding, sometimes failing, dealing with their own shadow-sides, and revisiting those stories over and over again to mine them for new truths, new perspectives, and even more complex versions of those stories.

As Alasdair MacIntyre calls it, interrogating the tradition’s

“sequences of decline as well as progress.”

I touched on an example of this earlier when I mentioned the story of the Underground Railroad we tell at Guilford College. There is a hagiographic way of telling the story – look at these good white Quakers who were early to work of abolition. But there is also a more powerful version that allows this story to become a “core story” in the way I mean when we tell the fuller story of the ways in which there was creative and redemptive aspects as people were faith to God, and ways in which corruption and rebellion against the justice of God was also at work.

In this second version, the Coffin family was among a few Quakers in this our area who were immediatists in their abolition. Many other Quakers were either gradualist, did not want to engage the issue, or were in favor of enslavement as was true throughout Quakerism up to that point. You then re-center the stories of the enslaved and emancipated Africans who worked closely with the other abolitionists (who were not just Quakers!).

Finally, trace these stories to the present struggles with racism, poverty, moral reasoning, and more. Investigate how the ways the institution has struggled and sometimes seriously failed around race and other justice related concerns, including the fact that a school – like Guilford – which was active in abolition did not integrate until the 1960s.

My colleagues Krishauna Hines-Gaither and Gwen Gosney Erickson did a fantastic presentation a couple years ago that shows how this kind of narrative, by mining it and developing it through multiple lenses and perspectives, can become an important core story to a community: Complicating Legacies: Slavery, Equity, & Inclusion on a Southern Quaker Campus.

I believe that these are the kind of stories that are powerful enough to shape the moral imagination and practices of a community long into the future.

Core practices work similarly and should be used to align with the Core Stories wherever possible. Instead of saying, we value Stewardship, develop institutional practices, procedures, and policies that are clear to anyone looking at them (and no less, participating in them) that these are indeed rooted in a community that is committed to being good stewards of what they have. Practices move beyond the surface, they are communal, adaptable, invitational and powerful. The whole community, whether you are new or born into this community long ago, can participate and in their participation will be shaped in the direction of the good of that community or tradition.

Another possible core practices for institutions wanting to be Quaker is to rethink their structures in ways that allow for a truly communal practice of decision-making. Rejecting the hierarchy, as usual, will not be easy, but taking structures that government or secular organizations and agencies use and trying to retro-fit Quaker practices onto it is a recipe for disaster.

Being practice focused allows the institution to rethink the whole thing – how can we integrate these practices in the best possible way? To practice community-wide decision-making well, people need to be onboarded well. People need to understand the core stories behind these practices. A practice focus is inclusive because it allows for those who are good or learn how to do the practices well to move from novice, to apprentice, to teacher and leader. One need not be an insider to participate in a practice in the same way that one needs to be an insider to understand all the unspoken rules, limitations, and barriers within an institution operating out of a birthright culture. Core stories and practices become the centerpiece and space where all of what we have discussed is integrated and put into action.

My hope is that there are things in here that are helpful whether you are in a Quaker organization or another faith-based group struggling with similar issues. These are very difficult times and very difficult practices to implement within larger institutions but as some of my friend Willie Baptist says: the struggle is the school.**

•◎•

This and the previous article are a distillation of my thinking and experience over the course of many years, which not only explains why it is so long, but why I may be still missing things (I have not yet experienced or been able to articulate)! This is an open-work! Please feel free to reach out with questions and feedback if you have any. Let me know what you think.

I am also happy to work with groups and communities who want to consider what it looks like to work these things out in their groups.

Footnotes:

*As an aside: For those of you interested in some of the scholarship that has influenced my thinking here, see Dandelion’s article, Testimony as Consequence, Not Values.

** Thanks Adam Barnes of the Kairos Center for illuminating me on this concept.

Query Reflection

- What do you see as the deep issues and causes keeping your institutions from both thriving and withstanding the religion of empire?

- Where do you see your own institutions struggling with similar and different trends discussed in this series?

- Which of the practices above do you think would benefit your community/institution?

- What action might you to bring about positive renewal within your institution using these or other ideas you are aware of?