The Emperor, Little Deaths and the Fig Tree (Lk 13:6-9)

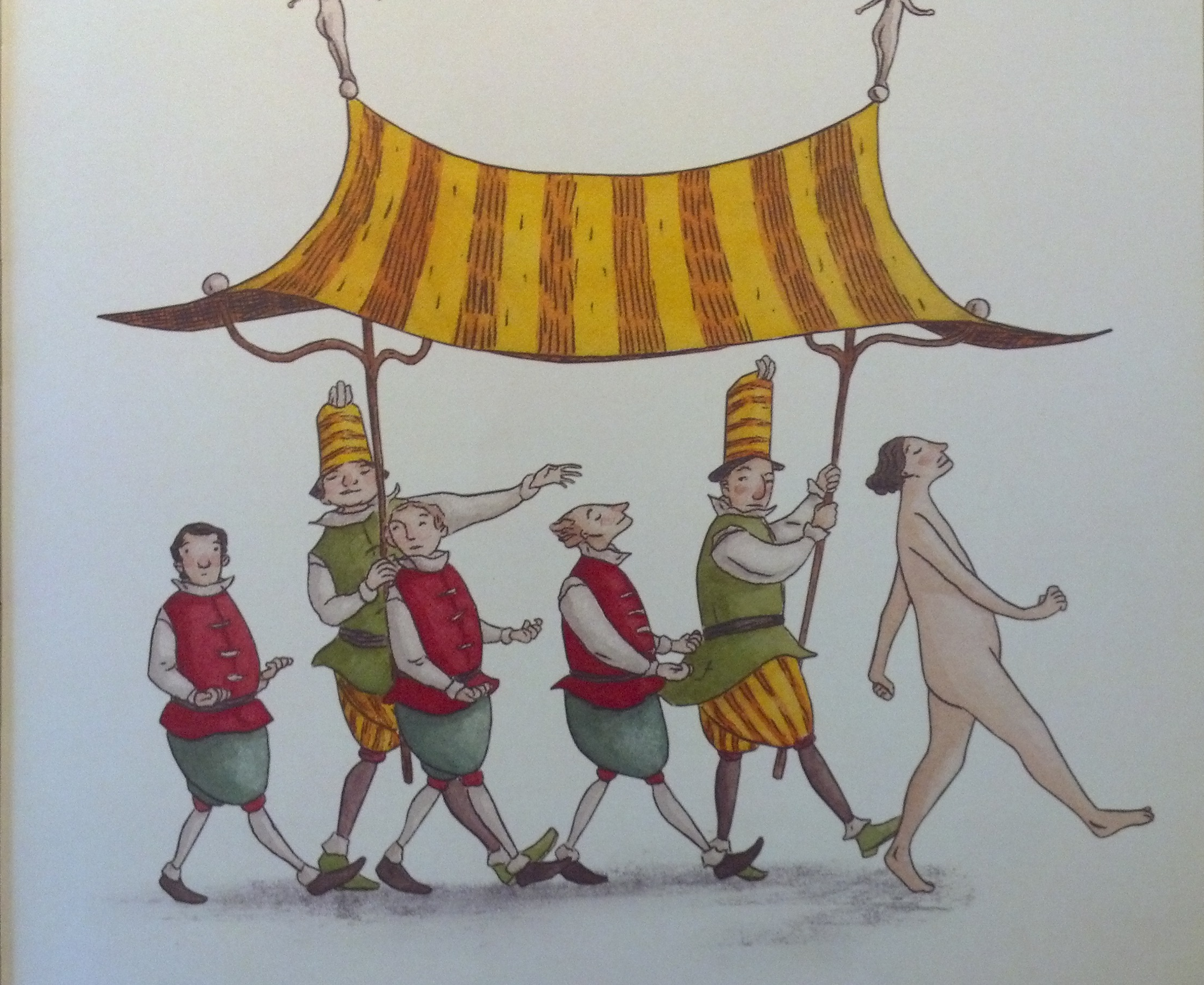

On Sunday we did a reader’s theater of the Hans Christen Andersen’s fable “The Emperor’s New Suit.” That helped set the stage for the rest of the discussion that followed.

Idols Create a false sense of self

During Lent, Michaela Bruzzese, says that “we are offered a unique opportunity to discard [our] false idols.”

Idols in our time can be anything that creates a false-self, layers us behind walls of protection, keeps us holding onto something so strong that inner change is unable to occur, or is an investment into “goods” that distract us from deeper and more meaningful ways of living in the world.

For the emperor his false idols were his ego and his vanity. For you and I it may be something different. We are all aware of those parts of our lives that can operate in the capacity of idols, none of us are beyond the reach of the Emperor’s story – even if that story is an extreme.

You are dust

What we do share, I believe, is a need to pass through the experience of what we might call “little deaths” from time to time, just as the emperor experienced a little death at the hand of some swindlers and a child.

This is not the “great death” that we all have no choice over.

Parker Palmer says that Little deaths are those experiences that “deepen our appreciation for life” and have the capacity to help move us towards a more undivided life.

A number of years ago when Emily and I were still attending Pasadena Mennonite Church we decided to attend an Ash Wednesday service. Mennonites tend to be more liturgical than Quakers and so we went as a good learning experience. It was much more than that for me. When the time came to spread the ashes on the forehead Jennifer, our pastor, called everyone to line up. And then one by one she spread a little ash on my forehead and said “Wess, Remember that you are Dust!”

Now I didn’t take this as a self-deprecatory statement. It didn’t encourage me into self-loathing, nor did it induce a feeling of guilt.

This little statement “Remember you are dust” is a description. It names reality.

I am made of earth and to earth I shall return.

I took this as an invitation to enter into a “little death” before I arrive at the great big one. It was an invitation to allow Christ to work in me a new kind of beauty and wholeness that will constantly evade me if I try to live as though I were a man made of steel, ageless, tireless; a machine without limits.

When death comes will I have produced with my life the kind of fruit I hope to leave behind?

Mary Oliver : When death comes

When death comes

like the hungry bear in autumn

when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse

to buy me, and snaps his purse shut;

when death comes like the measle-pox;

when death comes like an iceberg between the shoulder blades,

I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering;

what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?

[And therefore I look upon everything

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood,

and I look upon time as no more than an idea,

and I consider eternity as another possibility,

and I think of each life as a flower, as common

as a field daisy, and as singular,

and each name a comfortable music in the mouth

tending as all music does, toward silence,

and each body a lion of courage, and something

precious to the earth.]

When it’s over, I want to say: all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was a bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened

or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.

I love that she says “when death comes like an iceberg between the shoulder blades, I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering; what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?”

And —

“When it’s over, I want to say: all my life. I was a bride married to amazement. I was a bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.”

Little deaths can help to facilitate this kind of deep awareness and appreciation for life. They can, if we allow them, move us deeper into an undivided life.

Luke 13

In Luke 13 Jesus tells a parable about a fig tree that sheds light on both the Emperor’s New Suite and this movement of passing through “little deaths” to bearing new fruit in life.

Questions: What do you hear in this parable that resonates? What is the little death here?

This parable focuses on the sterility of the tree. The owner has had a enough. After three years of walking out to his vineyard in hopes of finding some tasty figs to put on his morning cereal he finds nothing at all!

This is a fig tree that makes no figs! What good is that? He says it’s worthless and should be cut down.

But here’s the interesting part.

The gardener disagrees with the owner. He says, “leave it alone. Give it another shot. I think you are wrong about this tree. If it gets a little more tending, if it drinks the right water, and eats the right food, it will begin to produce fruit.”

The gardener see that something is beautiful about the tree, something is still possible. That it can become a fruit-bearing tree despite its sterile past. But it needs some time, some effort and some care. It needs to confront its own “little death.”

Isn’t this true for us? We can find ourselves in a place where we feel we need a second lease on life. A second chance before God. This parable is about God being a God of second chances and Jesus as the gardener who sees the beauty of a tree that appears to be all but dead.

It is about the tree embracing a little death and I’d like to think that it goes on to produce fruit of its own in the coming years.

Like all of us it needs a little pruning, tending and the rich conditions, good food that produces an authentic and undivided life.

I think this telling of the parable is meant to open us up and make us reflect – do we choose life or death? Will we allow ourselves to be pruned, or will our destructive coarse lead only to further heartache and a divided life? Jesus invites his hearers to enter into a vulnerability.

Barbara Brown Taylor says about this text:

“It is not a bad thing for them to feel the full fragility of their lives. It is not a bad thing for them to count their breaths in the dark — not if it makes them turn toward the light.

“It is that turning he wants for them, which is why he tweaks their fear,” she writes. ” . . . That torn place your fear has opened up inside of you is a holy place. Look around while you are there. Pay attention to what you feel. It may hurt you to stay there and it may hurt you to see, but it is not the kind of hurt that leads to death. It is the kind that leads to life.

A New Story

I’d like to close with a re-writing of the Emperor’s story.

What if we were to re-write the story about the emperor and instead of the tailors being criminals they were Quakers who wanted to help strip the king of his falsehoods and help him facilitate an honest look at his life and what he was investing himself in?

What if in the story nakedness is a good thing, it represents a kind of integrity, transparency, a wholeness that we long for?

Our Quaker tailors were working to invite the King into a kind of “little death” to which he might move from sterility to fecundity.

The Child was the first to help him see it for himself because children are often able to see the inner beauty of others. They are able to see beyond the veil of lies, falsehoods and the “wisdom of the crowds.”

And instead of the king running off as soon as he found himself naked — as I would have done — he continues to march on in his birthday suite.

But in our story he doesn’t keep walking in order to keep up appearances, instead he walks because in that moment he had in fact entered fully into his own nakedness.

He accepted the little death, or George Fox’s once said, he passed through the flaming sword and into the paradise of God.

He was able to parade around in a new kind of naked beauty of the wholeness. He was able to enter that holy and torn place:

Look around while you are there. Pay attention to what you feel. It may hurt you to stay there and it may hurt you to see, but it is not the kind of hurt that leads to death. It is the kind that leads to life.