This is the second of a three-part post on whether or not Quakers can be “Publishers of Truth” today. In this series I want to talk about how I think early Quakers understood what it meant to be “publishers of truth” in earlier years (Part 1), just a couple challenges we face when it comes to a conversation about “truth” as Friends in 2017 (Part 2), and what it might look like for us to have a new the nursery of truth and be “Publishers of the pert near true” today (Part 3).*

Truthiness In All Its Beauty

In this second part, let’s look at what some of the challenges are to having a new emergence of publishers of truth today. I see at the very least three:

- Polarizations

- Whose Truth?

- The Role of Fantasy

Let’s take each in turn.

Polarizations

First, when we look at contemporary culture we have a serious truth problem. As I was preparing for this presentation, I was thinking back through some of the ways in which truth has been used, hijacked, and manipulated recently.

The most current examples are around fake news and alternative facts. Algorithms within social media make it easy for folks to be stuck within cloisters and once we’re mostly surrounded by people who look, think and feel like us, it is very easy to control a narrative with memes and other newsy-looking blog posts and articles that are really fake news.

Fake news is bad enough, but when you reinforce it with a sense of community, where everyone you know is consuming the same kind of messages you get the potential for quickly spreading falsehoods and dangerous behavior.

In his book, “The Big Sort,” Bishop writes:

America may be more diverse than ever coast to coast, but the places where we live are becoming increasingly crowded with people who live, think, and vote like we do. This social transformation didn’t happen by accident. We’ve built a country where we can all choose the neighborhood and church and news show — most compatible with our lifestyle and beliefs. And we are living with the consequences of this way-of-life segregation. Our country has become so polarized, so ideologically inbred, that people don’t know and can’t understand those who live just a few miles away.

This first challenge to truth is one of polarization that is reinforced by the combination of fake news and a cloistered community. Within these groups, and let’s be clear that this happens on both sides, conservatives and liberals, are caught within this trend, there is a lack of diversity of ideas, lack of diversity of outlook and perspective and a lack of difference when it comes to personal experiences that we might draw on to challenge these trends. I have also seen a growing unwillingness to even hear what the other side might have to say. There is a lack of humanizing one another and seeing each other as more complex than a vote, or from a certain class, a skin color, or a sexual orientation, etc. This kind of fake news and gossip easily feeds into our confirmation biases, they fuel anger and resentment, and they reinforce a sense of us over and against them.

Whose Truth?

A second challenge is the adjudicating between various truths within competing traditions. To put it shortly, for all its necessity and benefits pluralism opens up new challenges for thinking about what truth is and how to communicate it. The other day I made the observation in a meeting where some of us were talking about forgiveness that within the context where we were speaking there was very little shared reference point for talking about forgiveness as a personal practice let alone some kind of shared communal practice.

Where do we find shared ground to speak from? How do we begin to think about ideas of good and bad, right and wrong? Is it possible to “publish truth” today and must it always be limited to the personal “my truth,” or are there ways in communities and traditions can speak truth without falling into the traps of patriarchialism, white supremecy and other forms of oppressive truth?

On the one hand, you have the tradition of the Enlightenment which says that truth is derived from human reason, science and facts. This approach gives us the scientific method, it gives us the Encyclopedia Britannica, it gives us objective modes of writing about history, theology, philosophy, sociology, anthropology, and more. It also gives us colonialism and the construction of race as an idea. Both liberal and conservative faith traditions that we are accustomed to within the Quaker tradition take their cues from this epistemology of truth; liberals folks tend to rest the authority of human knowledge on individual human experiences, while conservative folks rest it upon a sacred text. Both are foundationalist. Both are indubitable. Both cannot be called into question or the whole thing comes tumbling down.

A challenge to this viewpoint is the postmodern tradition and its viewpoint on truth, i.e. postfoundationalism (See Ethics Vol. 1 – Wm. James McClendon, Jr.). For this particular tradition, truth is about the power and privilege. The philosopher Micheal Foucault is famous for his work on truth and power, talking about things such as “regimes of truth” and arguing that “power is everywhere.” For Foucault, only one postmodern thinker, not all power is negative but says:

‘We must cease once and for all to describe the effects of power in negative terms: it ‘excludes’, it ‘represses’, it ‘censors’, it ‘abstracts’, it ‘masks’, it ‘conceals’. In fact power produces; it produces reality; it produces domains of objects and rituals of truth. The individual and the knowledge that may be gained of him belong to this production’ (Foucault 1991: 194).

Without the postmodern critique, we have struggled to really put together a productive counter-narrative to the dominant narrative of the Western Enlightenment. On the other hand, there are some very real ways in which this viewpoint has also made truth more challenging to assert in any kind of universal way.

As Ken Wilbur points out:

Truth, rather, was a cultural construction, and what anybody actually called “truth” was simply what some culture somewhere had managed to convince its members was truth—but there is no actually existing, given, real thing called “truth” that is simply sitting around and awaiting discovery, any more than there is a single universally correct hem length which it is clothes designers’ job to discover. (Ken Wilbur, 5)

I believe that The challenge for truth here is that there is a fragmentation with many competing perspectives, approaches and even criteria for what is or is not true depending on your particular tradition, culture, social location, etc. In so many ways this is exactly what we need. For far too long the regimes of truth have been white straight cisgendered land-owning Christian men (often also educated and wealthy) in this country and as long as you worked from their perspective you had “objective” and unbiased truth. I think we needed this fragmentation to begin to break all of this up and challenge it and get some space from it so something new can arise. However, for the many ways in which pluralism is right, it still leaves some out and it makes it seems to be more and more challenging to find a place from which to stand and speak as a collective.

Fantasy

Finally, one last challenge I see is that progressives need to be more creative with the truth. Drawing on Stephen Duncombe’s fantastic book, Dream: Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy, argues that:

“We live in a ‘society of the spectacle,’…Yet, faced with this new world, progressives are still acting out a script inherited from the past.”

Duncombe’s point is that while the Right continues to spin false narratives and alternative facts, Progressives are woefully slow and ineffective in their responses, especially when they focus on truth as cold hard data and facts stripped of any kind of narrative or human emotion.

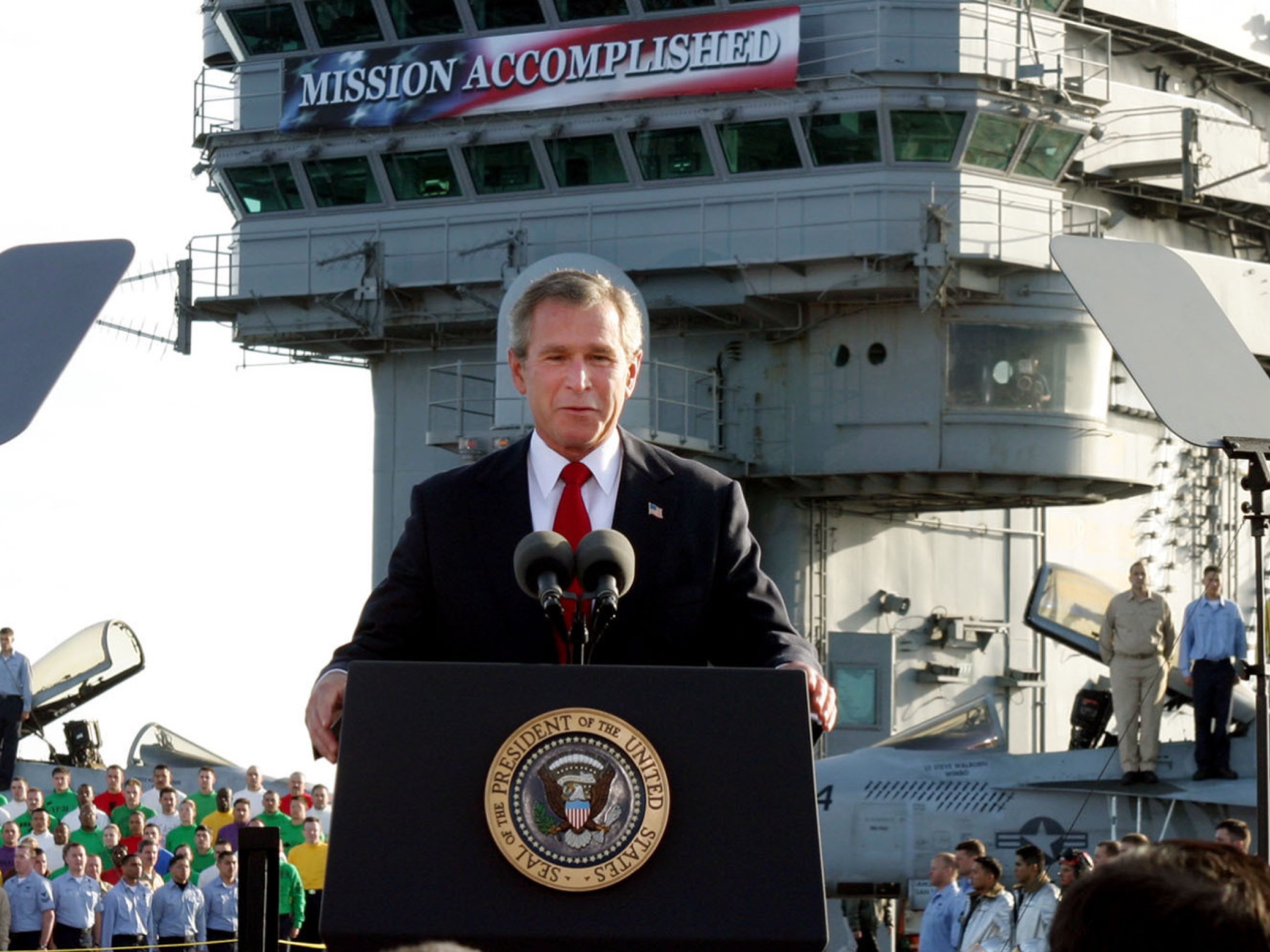

Remember when George W. Bush gave the mission accomplished speech about the war in Iraq in 2003? It was a Photo-Op that took place on the aircraft carrier the USS Abraham Lincoln. The point of the speech was to say that the war had ended in Iraq, which as we all know now was calling just a tidbit too soon.

Or consider Stephen Colbert’s Correspondent’s Dinner for George W. Bush

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CWqzLgDc030&w=560&h=315]

“Look it up in your gut.” And as much as I think this is hilarious and as troubling as it is, there is a very real sense in which this hits some serious nerve. Colbert’s success was that he was able to challenge dominant political ideas by using powerful imagerary, story, character acting and especially satire. Unless progressives are able to reframe facts in ways that make sense to the real “gut” concerns of everyday folks, remaining behind an intellectual veil (Duncombe, 10).

The point I’m trying to make here is not that progressive and Quakers who identify as such should do this kind of manufacturing of consent. We should also be very clearly ethical and integral in all we do, but I think that progressives have often lost the way because we have elevated objective fact and ignored the reality of the power of story, image, metaphor and people’s emotional responses to things.

Duncombe again says:

“Progressives should have learned to build a politics that embraces the dreams of people and fashions spectacles which give them fantasies form – a politics that understands desire and speaks to the irrational; a politics that employs symbols and associations; a politics that tells good stories. In brief, we should have learned how to manufacture dissent. 9

This kind of Enlightenment truth for progressives can lead to a kind of smugness, as though thinking, “If only they had access to the truth the way we do then the scales would surely fall from their eyes and see (Duncombe, 6-7).” For one, I see a lack of compassion and empathty in this view. For another, we know this isn’t really true, everything we know and experience is, as Duncombe says, “refracted through the imagination.” Because of that it is not enough to just work with “reality,” we have to address story, the emotional and the irrational (18).

Emily Dickinson put it like this:

And Quaker minister Peggy Morrison in her book, Miracle Motors, call it the pert near true:

“Pert near true is a story that has so much truth to it, that it doesn’t really matter whether it happened or not.”

Morrison suggestions that while John Woolman may not have appreciated this idea, this is very much the kind of framework Jesus was working from as he traveled around teaching in an oral culture. Plus, this approach can be a lot of fun and help to loosen things up a bit!

This post is one of three in a series. You can read the first post here and the last post here (to be published April 19, 2017).

This was a talk given at Quakers United in Publication St. Helena’s Island, South Carolina @ William Penn Center March 2017. For another paper on this topic from a different direction, you can go here.