This is the sermon I preached Sunday January 16, 2011.

The want of peace_

One of the queries I sent out for reflection this week over email to the church was “how do we support peace?” How do I, Wess Daniels, We the Daniels Family, We Camas Friends Church, support peace?

But I also wondered. What does it mean to support peace, to really want it? Because it’s one thing to put a bumper sticker on your scooter, as I’ve done, it’s quite another thing to actively pursue peace in a 20 year family conflict, to try and reconcile with a brother who has deeply wounded you, to step outside your front door and begin nurturing relationships with your neighbors that might actually produce fruits of peace.

A friend of mine is known for being a peacemaker in his neighborhood. Each fourth of July he and his wife throw party for their entire block and everyone comes out because he’s literally befriended most of his neighborhood. If you hang out with him over the course of 3 hours 3 or 4 neighbors will randomly drop by to say hello, drop off cookies, or some little treat for his children. It’s unreal. How many of us don’t even know the names of our neighbors let alone actually create space where relationships can grow and neighborhood peace can be nurtured?

I’m reminded of Don and Joy’s presence in their friends’ life as she past away and their care for her family since then — this is a perfect example of nurturing and supporting peace in a neighborhood.

Do we want peace and how do we support it?

I loved what Heather had to say last week and one thing she said that has stuck with me is:

When relationships are broken, when there is distrust, when we cannot speak to that which we are, then community is non-existent. We can also say that peace is non-existent.

In order to support it we have to want it, we have to develop a desire for peace because our world does not nurture a desire or hunger for peace.

The Want of Peace by Wendell Berry

All goes back to the earth,

and so I do not desire

pride of excess or power,

but the contentments made

by men who have had little:

the fisherman’s silence

receiving the river’s grace,

the gardener’s musing on rows.

I lack the peace of simple things.

I am never wholly in place.

I find no peace or grace.

We sell the world to buy fire,

our way lighted by burning men,

and that has bent my mind

and made me think of darkness

and wish for the dumb life of roots.

Our minds are “bent” to think of darkness, of selfishness, to envy, to be proud and deceiving, but this is not the way we were created, nor is this the way that life is meant to be. How do we cultivate in ourselves, in our children, and in our grandchildren this quality:

I do not desire

pride of excess or power,

but the contentments made

by [people] who have had little:

We need to nurture this desire in ourselves. It might be a natural desire within us to want peace as Isaac Penington says:

“There is a desire in all men (in whom the

principle of God is not wholly slain) after

righteousness; which desire will be more and

more kindled by God in the nations, before

righteousness and peace meet together and be

established in them.”

But it is by no means a natural desire within the culture we live today.

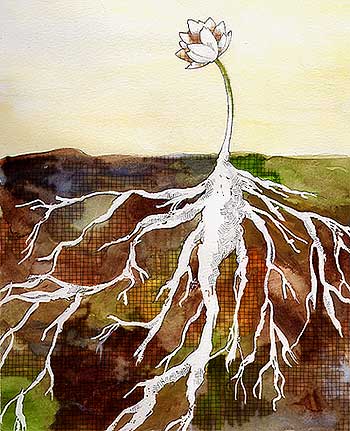

We find no peace until we become like the “life of roots” that is, the way things were intended to be, where we return to a “first simplicity,” a deep sense of community, and equality with others.

Path of Death_

Instead it seems that, as one theologian put it:

Our society has chosen a path of death in which we have reduced everything to a commodity. We believe that there are technical solutions to everything, so it doesn’t matter whether you talk about the over-reliance on technology, the mad pursuit of commodity goods, our passion for violence now expressed as our war policies. All of those are interrelated to each other and none of us, very few of us, really want to have that exposed as an inadequate and dehumanizing way to live.

Much of what shapes us, guides us, entertains us, much of what we see on the TV or that we show our kids, much of what is sold to us in the stores, much of what we hear talked about from politicians, and read about in books is related death and dehumanization. It points us on a path towards violence and death.

Violence is anything but a crucible for peace. Violence leads us down a path of death.

And violence is far more complex than punching or shooting someone. Let’s identify some of the many forms of violence in our world:

1. Obviously we know that Violence can be physical harm.

Physical violence is something we can do to others, to our enemies and to our friends and family, we have witnessed too often horrific violence done upon spouses and children. The recent Washougal episode is but one recent example. But physical violence is also something we can do to ourselves in many different ways from the way we eat, to the way we work, to the way we rest, and on and on.

Physical violence, I suppose, as with all violence almost always has behind it anger, despair, retaliation, envy, greed, oppression. On the other hand, peace works to undo these things.

2. But Violence can also be done through “symbols” and language.

The way we talk to one another. The images that are used to represent people, our body language. Stone-walling one another. I think about the myriad of examples of how women are represented in the media, and specifically women’s bodies.

‘Twenty years ago the average fashion model weighed 8% less than the average woman. Today, she weighs 23% less.’ and ‘The majority of plus-size models on agency boards are between a size 6 and 14, [while they used to be between 12-18] while the customers continue to express their dissatisfaction.’

This is a kind of “symbolic” violence. We know what this does to the psyche of people everywhere.

Another is with the conservative Christian position of “The husband is the head of the household,” which, at least in my experience, often means silencing the woman on important issues that she should have had a voice on. This is violence through symbols and language, using your position or words to shut other people down.

3. Finally, there is systemic violence.

Violence that oppresses that we may participate in and yet have very little to say about it. We read about systemic violence when we read the book of exodus and Pharaoh’s oppression of the Hebrew people. We read about systemic violence when we remember the civil rights struggle.

Just last night I was reading about the Sanitation workers strike in Memphis back in 1968 where two young black men had been killed because of faulty sanitation equipment, equipment these young black men had been pleading with city officials to replace but they wouldn’t, not even after the men were killed. This is systemic violence.

Early Friends understood our implications in systemic violence when a number of them refused to pay war tax, or tax money that funded violent means. When we purchase things knowingly or unknowingly produced in unfair and unsafe working conditions, this is systemic violence.

A friend told me about her trip to the Philly Student Union which is a group of students from some of the poorest and worst schools in the nation. When they were asked how they dealt with such high rates of gun violence, they said that that wasn’t even the real issues of violence that they faced everyday. They face violence of a systemic kind such as the kind that hurts their chances for better education, the lack of opportunities, the lack of resources from books to healthy food, etc. They said, now remember these are students in really “bad” schools, the kind of violence that teaches them to fear their neighbors rather than those who really hurt them.

Today there is still systemic violence among immigrants, African-Americans, and many other “marginalized people” in our society.

When asked how they understand what “violence” means the students a part of the student union said:

violence is “power that hurts”

peace is “power that helps.”

What we are called to as followers of Jesus, and as the Quaker church is to use our resources, to use the power we have (and you’d be surprised, when compared to a lot of folks, like these students in Philly) to help and support those who experience these kinds of violences we can exploit our own privilege for others gain.

I believe this is what the peace testimony is about.

Peace is a Garden_

At the opening of Berry’s poem he writes “All goes back to the earth” even our metaphors for peace. There is no direct way to obtain peace. There is no fast and quick, easy-to-go methods to challenge such complexities in our world.

You can’t have peace unless you put yourself to the work of growing the seeds of peace. The reason why we have wars and violence (personal and global) in our world isn’t because we don’t have people who want peace. It is because we have not done the work of planting the seeds of peace and growing that peace, tilling it, fertilizing it, caring for it, nurturing it. Instead we’ve let the weeds of greed, of selfishness grow up around our seeds.

We’ve let the birds of envy and hatred come and feed on the seeds of peace.

The weeds of discord can easily overgrow the seeds of peace.

Take the nutrients those seeds need and suck us dry of hope and love.

The weeds can block the light for the seeds of peace.

And without the Light, warm and visible, there will be no peace.

Peace is a garden. And if it is not tended to it will not grow.

Peace is a garden. The vegetation that grows from its roots are righteousness and justice.

Peace is a garden where we are all called to be gardeners, tenders, and laborers of the fields.

James contrasts these two gardens of conflict when he says:

James 3:13 Who is wise and understanding among you? Show by your good life that your works are done with gentleness born of wisdom. 14 But if you have bitter envy and selfish ambition in your hearts, do not be boastful and false to the truth. 15 Such wisdom does not come down from above, but is earthly, unspiritual, devilish. 16 For where there is envy and selfish ambition, there will also be disorder and wickedness of every kind. 17 But the wisdom from above is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, willing to yield, full of mercy and good fruits, without a trace of partiality or hypocrisy. 18 And a harvest of righteousness is sown in peace for those who make peace.

“a harvest of righteousness is sown in peace for those who make peace” it’s the only way.

And so, if peace is a garden the “children of God” are to be the sowers of the seeds of peace.

These sowers nurture their soil to build its capacity for growing beautiful and healthy harvests of righteousness, justice and peace.

These sowers will grow the capacity to be with those whom they disagree with.

These sowers will grow the capacity to love others and forgive others. They will not retaliate.

These sowers of peace will work towards living a life that has no enemies.

These sowers of the tender seeds of peace believe that there is something to be learned from everyone. And that each and every human life is a child of God and who mirrors the image of God.

These sowers of peace will use whatever means and power they have to help others (as those others are a part of them and guide them).

These sowers will love the unloved, the ones desperate for love, the hopeless and hurting, the marginalized in our world.

These sowers will be sowers of peace because of their deep sense of patience and trust in God’s power, God’s mercy and God’s love for all people.

Peace is a garden because there is no short-cut way to bring about change in today’s world. As Wendell Berry says, “So as gardeners musing over rows” we, the sowers of peace, must continue to cultivate and grow peace in each of our homes, in our neighborhoods, in each of our souls, in each of our marriages, and families and all the relationships we attend to. It sounds small, but that’s just the way it is.

As Elise Boulding “There is no time left for anything but to make peacework a dimension of our every waking activity.”

Let us take on this work.