On Choosing the Golden Calf or the Lamb

“When the people saw that Moses delayed to come down from the mountain, the people gathered around Aaron, and said to him, “Come, make gods for us, who shall go before us; as for this Moses, the man who brought us up out of the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him.” Aaron said to them, “Take off the gold rings that are on the ears of your wives, your sons, and your daughters, and bring them to me.” So all the people took off the gold rings from their ears, and brought them to Aaron. He took the gold from them, formed it in a mold, and cast an image of a calf; and they said, “These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt!” When Aaron saw this, he built an altar before it; and Aaron made proclamation and said, “Tomorrow shall be a festival to the LORD.” They rose early the next day, and offered burnt offerings and brought sacrifices of well-being; and the people sat down to eat and drink, and rose up to revel.”

(Exodus 32:1-6 NRSV)

This is a message I gave at First Friends Meeting on November 17, 2024.

This is the query I'm working with this morning: What do we do in uncertain times and where should we turn?

The Stories We're Rooted In And How We Tell Them

One of the things I do in my day job at Guilford College is give a lot of Underground Railroad tours, mostly to kids in primary and middle school. I’m not exaggerating when I say we’ve had close to 600 k-12 students from surrounding NC schools back to experience this UGRR Tour in the last 6 weeks alone. It’s pretty amazing to have the opportunity to share that story with students, and it remains astonishingly relevant as a story of how Quakers, Enslaved and Freed Blacks, and other allies responded to injustice and uncertainty in their time.

Every time I tell these stories under the canopy of the Guilford woods, I find inspiration about the kinds of choices Friends made despite the challenges and uncertainties they faced.

Exodus is in many ways that same story just further back in the tradition of resistance. It is the story of God liberating the people out of the slavery and oppression of empire. It is no wonder then that Enslaved Africans on this continent were drawn to the stories within this book: a book that has no qualms claiming that God takes the side of the poor and was at work to deliver them.

I believe whether it was in the time of Exodus, during Slavery, or in our own time, it is up to us to choose to find ways to join God’s work of liberation and love in the world. And stories like this absolutely help with this.

What I find really interesting about the story of the Golden Calf is it reveals something about the power of trust and choice in anxious times and how that community can and should respond.

If one of the main point of Exodus is about God liberating the people out of empire, it is also very much about how those people responded once they are free.

Commentators and preachers alike have spilled plenty of ink criticizing the Hebrew people for their seeming lack of faith:

“How could you grumble and want to go back to Slavery in Egypt!” “How ungrateful could they be?”

I have heard too many sermons poking at the Hebrews as though they were spoiled babies, rather than seeking to empathize with a community of marginalize people newly freed and processing their own imperial trauma.

It is not too hard to imagine how we might want to go back to a place of certainty when the current reality was washed in anxiety and the unknown.

Instead, I see these stories as being a kind of “wilderness school” where the people were meant to learn the lessons of how to not become like empire.

God led the people out of Egypt not to become another Egypt but an alternative community that lived in contrast in every way to where they just left. It takes a lot of work and unlearning to be formed in this alternative vision.

- This explains the importance of the 10 commandments, not as a set of domineering rules enforced on people, but as guardrails for how not to become like the place they just left.

- Or how about God providing Manna in the wilderness, nourishment to keep the people going. The lesson there was to only take what they needed for their families. Manna is a story about generosity, sharing, and refusing to hoard; a contrast to the extraction, hoarding, and wage theft of empire.

To put it into a well-known phrase Franciscan phrase, the lesson was to live simply so that others can simply live (Link).

Losing Site of Trust

The story of the Golden Calf then follows this line of thinking. In a time of high anxiety and uncertainty, the people turn back to the god of empire.

When Moses did not return down the mountain for forty days, that was enough time for the people to lose trust, which to be honest, I can empathize with.

When I was a kid and my mom asked me to wait in the car while she quickly ran into the grocery store, it took me about 5 mins before I was ready to call out the search party. I was sure she was never coming back.

Whether the forty days is literal or just a literary device, the idea holds: the people in Moses’ absence lose their trust in him, and YHWH, and turn back to their default mode that they had been shaped by the religion of empire.

The story exposes the choice that is made in this moment, which tells me that there are other choices they could have made as well.

While we often associate the Golden Calf today with the idolatry of money, for instance the Charging Bull outside Wall Street, we should see what is happening in this story as instance of empire trying to reassert itself religiously.

This semester I have been working with some students on trying to understand Christian Nationalism. Christian Nationalism in America today is empire trying to reassert itself religiously.

The formative, liturgical powers of empire, are powerful. They were willing to give up all the gold they plundered from their enslavers to recreate this false god.

Walter Brueggeman says of this passage, Aaron makes the calf builds an altar and,

“Consolidates this new theological arrangement by building an altar, proclaiming a festival, and receiving offerings (v. 5-6). That is, Aaron authorizes and constitutes a full alternative liturgical practice. His lame excuse - "we don't know what has become of him!..."

Empire has its own theology that wishes to shape and form us as people. The religion of empire can become a default mode for us in our relationships with each other (casting one another in us vs them terms), in our thinking about economics (abidance for a few at the expense of everyone else), in who we deem worthy of help (only those who are like us), and in our political framing (who can be scapegoated to avoid the real issues).

That is why I really like thinking about the idea of the Golden Calf as a religious symbol that shapes a “liturgical practice.” Living in the America today, there are most certainly liturgical practices of empire that are meant to shape us. But that also means that there are liturgies of resistance as well. (But that’s a message for another day).

In an anxious state, the people chose to return to a god of empire, the god of certainty, which betrays their lack of trust for Moses and YHWH who had delivered them.

Theirs was just a choice, not a foregone conclusion.

What We Choose

This is what I bring to you today. In our own time, we are also faced with similar choices. To allow our anxiety and uncertainty of today to give into a default mode of ourselves acting like people of empire, living in a kind of paralyzed fear; or we choose a different path, one based on building relationships of trust, and following the commitments that have made Friends who we are.

If we can choose empire, we can also choose to serve a God who is on the side of the marginalized and oppressed.

We stand in a faith tradition that has understood this and stood for this. Friends throughout time have lived lives of faithfulness in the face of fear and uncertainty.

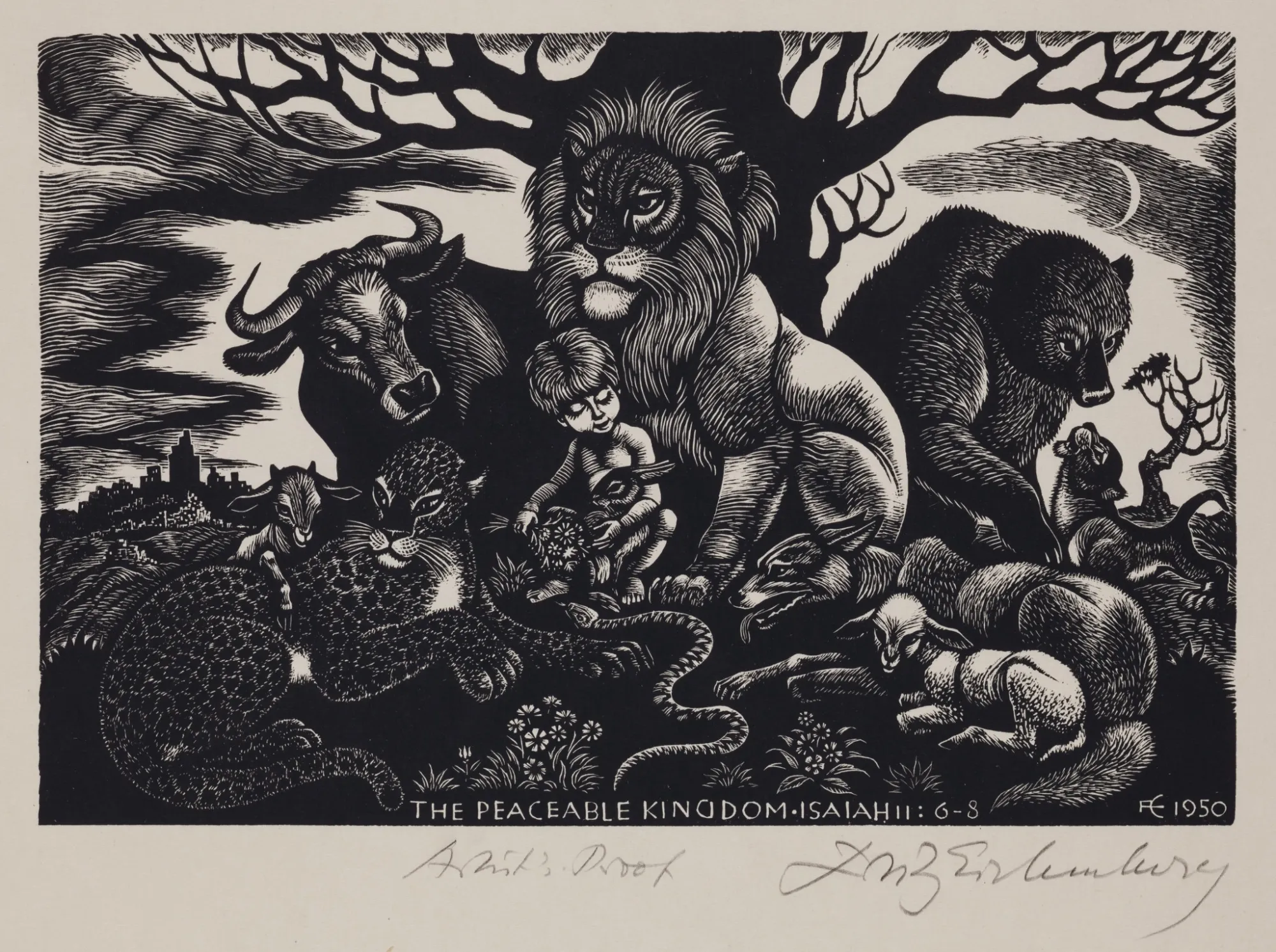

And when things got really hard, they did not fashion for themselves a false god of empire, but remained committed to alternative image: the lamb that was slain from the book of Revelation. Sometimes referring to it as “the war of the Lamb (a metaphor for the struggle against powers and principalities)”

So if the Calf represents the religion of empire,

The lamb is the image of a God who stands with the victims of empire.

If the Calf represents an economics of exploitation,

The lamb stands for love and abundance for all people and all creation.

If the Calf images a world controlled by fear and anxiety,

The lamb embodies a world freed by deep courage and hope.

As George Fox once said:

I saw the infinite love of God. I saw also that there was an ocean of darkness and death, but an infinite ocean of light and love, which flowed over the ocean of darkness. And in that also I saw the infinite love of God...

Friends, it is for us, in every generation to make a choice, standing at the bottom of the mountain unsure of where God has gone, faced with the unknowing darkness ahead, and instead of returning to the gods of empire that seek to undermine that Spirit of love:

Let us choose courage and hope, when that is the last thing we have.

Let us choose to listen for the truth that affirms, even as all that is shouted are lies that tear down.

Let us choose to build relationships of trust, so that we might recreate networks of freedom.

Let us choose to love where hate seeks to smoother out goodness.

Let us choose discomfort, knowing that God is going to trouble the waters of empire.

Let us choose to immerse ourselves in Biblical and Quaker stories of freedom and liberation, so faith does not falter.

And let us choose the image of the lamb, resisting the false god of empire.

May that image of sacrificial love, nonviolence, and truth-telling be what shapes our generations as we choose to stand with those who suffer until again we see the beloved community abound.