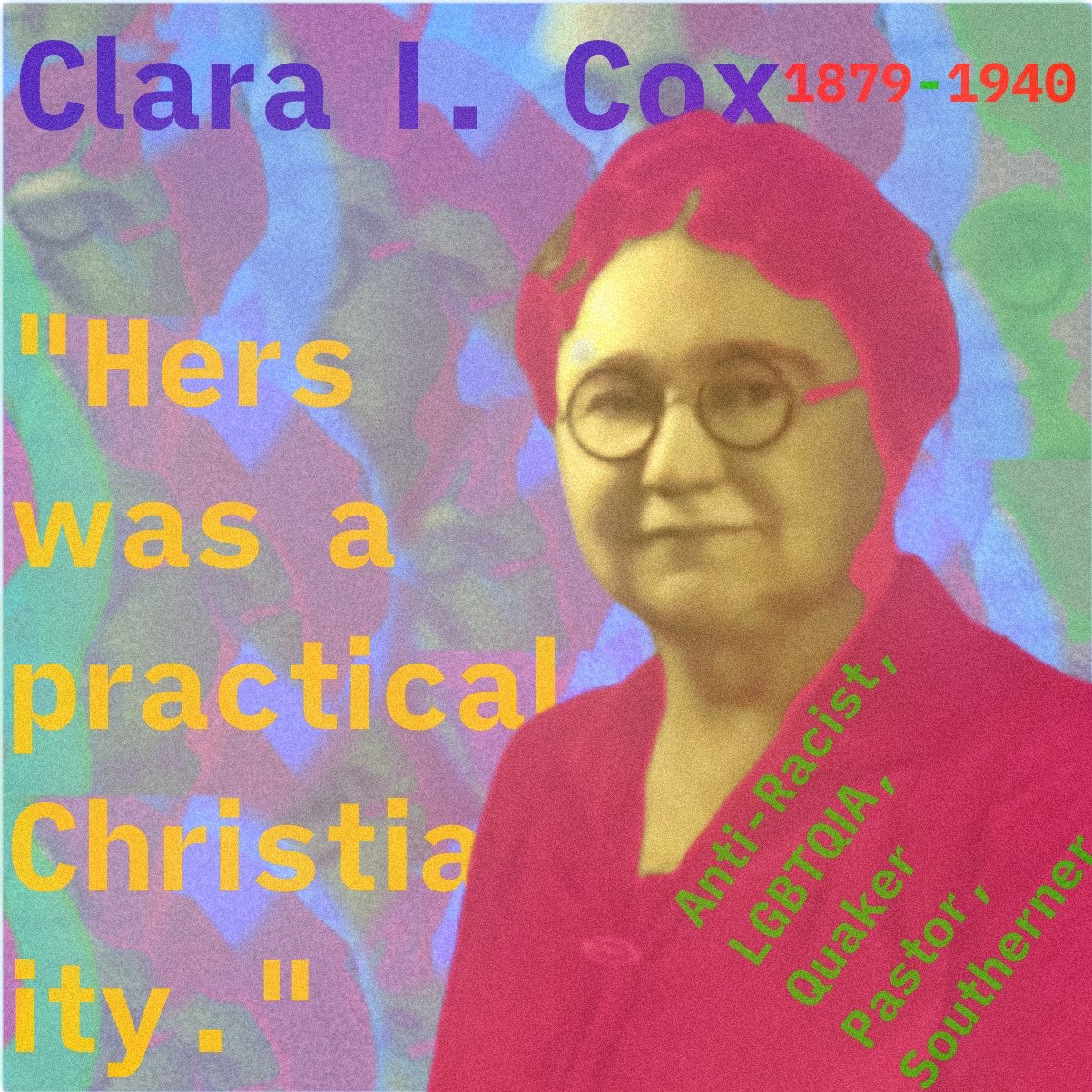

Clara Ione Cox – A Little Quaker Pastor Inspiration During Pride Month

This is a post I wrote as a part of series we’re working on at Friends Center to celebrate Pride by lifting up Quakers who were also part of the LGBTQIA+ family.

I first met Clara when I visited the Quaker Archives at Guilford College shortly after my arrival to Greensboro, NC in 2015. Living out in the Pacific Northwest, I knew many Quakers who didn’t fit into a nice, neat, “Quakerly” box. Few were Quakers from long lines of Quaker families. Many came to Quakerism after some change, transition, or looking for an alternative faith community that was different than what was generally on offer. Most of my heroes have been people who don’t fit the mold in one way or another. I guess I like these people because I’ve experienced life as an outsider and know well the inner walls of “imposter syndrome”. I imagine that many of these feelings and experiences were true for Clara Ione Cox as well. When Gwen Gosney Erickson, Quaker Archivist at Guilford, first told me about Clara, I knew I found my person.

Clara I.Cox (1879-1940), as she preferred, was a Quaker pastor during a time when being a female-identified pastor was not all that popular nor accepted, and when being a Quaker pastor was questioned by many Friends (as it continues to be for some today).

There were other lines blurred in Clara’s life: she was a staunch advocate for the poor even though she was born into a wealthy family she chose to give what her parents gave to her – so she would fit in better among “proper” society – away as a means of supporting the poor. After her death, 250 housing units complex for the poor was named in her honor.

Even though she was a white Southerner, she was heavily involved in anti-racist work and was known to be a friend and trusted ally by many leading African-American leaders in North Carolina. She was the chair-person for the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. A white woman standing up against the vicious mob and scapegoat mentality of lynching took tremendous courage. And she was born intersex during a time when that was not well understood or treated as a normal thing. They said she was on “abnormal birth.” She never married or partnered, but had a cousin, or a friend, we are not completely sure (which already says something, doesn’t it) live with her and take care of her until Clara died in 1940.

Many Friends during this time were unfortunately of the “separate but equal” perspective. Clara challenged this with her life, her public ministry and witness, and in gatherings she promoted. For instance, she was in attendance at an Interracial Quaker Gathering in Greensboro in 1928 that was hosted by Greensboro Monthly Meeting, today as First Friends Meeting. In attendance were prominent Northern Quakers like Henry T. Cadury and Rufus M. Jones, along with “active and influential NC Friends: Clara Cox, Marvin Shore, and Hugh Moore. All three were Guilford graduates” (Gwen Erickson).

“In his eulogy written for Clara Ione Cox upon her death in 1940, Joseph H. Peele states, “her last official message was an earnest request that Interracial Sunday, which comes on the eleventh of this month, be properly observed” (Omeka.net)

At the end of her life, one newspaper clipping said of Cox, “Hers was a practical Christianity.” To me, Clara is a symbol of the kind of convergent, punk-rock Quakerism that continues to inspire me most.

-Wess Daniels

*I also want to say I was greatly helped by Brenda Haworths biography of Clara Cox (her work is quoted below).

The more “Encyclopedia” version of this write-up:

Clara Ione Cox was an only child, born to Bertha and Ellwood Cox in December 18, 1879. Bertha and Ellwood were devoted Quakers and deeply connected to the early life of Guilford College. Cox was also born intersex at a time when this was not well understood or accepted. She was, however, accepted by her family and many within the Quaker community.

And though she never married, Effie Cox, possibly a cousin, lived with Clara, and her Mom and Dad, until after Clara’s death. Effie “became her foster sister, companion, dressmaker, secretary and home manager” (Haworth, 1994: 14). Many of her records were destroyed so we do not know how she thought about her own identity (Gwen Gosney Erickson, “No Ordinary Daughter: Clara I. Cox’s Many Ministries,” Unpublished: 2021.)

Cox is remembered today for three main things that all integrated throughout her life and faith: her commitment to being a Quaker pastor, her leadership in the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, and her commitment to the poor. Each of these were the consequences of her own faith in God and identity as a Quaker.

Cox graduated from Guilford College and, due to a calling to enter the ministry, attended seminary in New York. She was a noted recorded Quaker Minister of Springfield Quaker Meeting in North Carolina for twenty-one years (she also served Archdale Meeting during some of this time). In her role as as the president of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching she corresponded with prominent leaders and activists, both white and black, like Jessie Daniel Ames, C.C. Spaulding, Charlotte Hawkins Brown, and many others. She advocated for the prevention of lynching through personal and public correspondence and work on various interracial projects related to education, politics, and poverty (Erickson, Cf. lynching.omeka.Net). Lastly, she was deeply concerned with the poor, and did what she was able to address poverty in and around the High Point area (leading to a 1942 public housing complex of 250 units in High Point being named in her honor).

Two quotes from Brenda Haworth’s biography of Cox are illuminating on this point:

“Her parents had decided she should take her place as a leader in High Point society. To their disappointment Miss Clara showed no aptitude for that kind of life. While they supplied her with lovely clothes, money and opportunities in society, she was only interested in using the clothes and money to help the less fortunate” (Haworth, 1994:15).

“Most of Miss Clara’s energy, talent, and love went to people, especially the poor. Her concern was great enough to especially anyone in need. Every day found her in her car going to someone’s home to comfort, help, cheer, or simply visit. One newspaper account described her visits as “bits of kindness here and there, a helping hand unobtrusively extended, warm, eager words to assuage grief, to bring cheer, to bulwark courage and the will to forge on.” (Haworth, 1994:16).

Lastly, Cox worked among Quakers to change hearts and minds. Many Friends during this time were of the “separate but equal” perspective still, she challenged this with her life, her public ministry and witness, and in gatherings she promoted. For instance, she was in attendance at an Interracial Quaker Gathering in Greensboro in 1928 that was hosted by Greensboro Monthly Meeting, today it is known as First Friends Meeting. In attendance were Quakers prominent Northern Quakers like Henry T. Cadury and Rufus M. Jones, along with a “active and influential NC Friends: Clara Cox, Marvin Shore, and Hugh Moore. All three were Guilford graduates” (Erickson).

“In his eulogy written for Clara Ione Cox upon her death in 1940, Joseph H. Peele states, “her last official message was an earnest request that Interracial Sunday, which comes on the eleventh of this month, be properly observed” (Omeka.net)

At the end of her life, one newspaper clipping said of Cox, “Hers was a practical Christianity.”