Building a Participatory Pedagogy

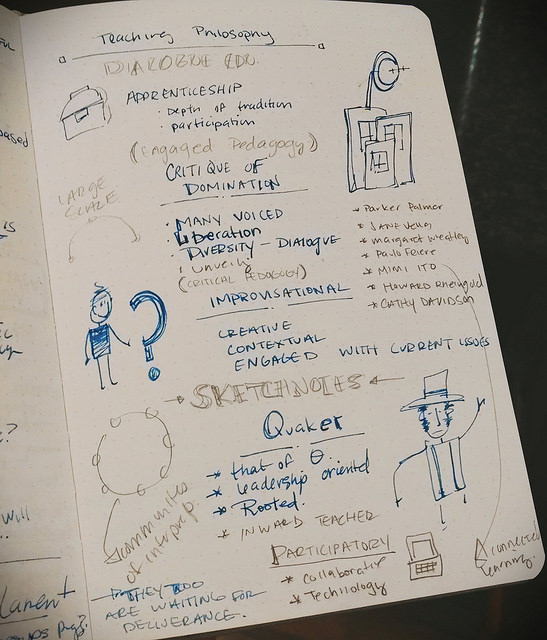

Given my love for teaching, and my forced time off this winter semester, a time I would typically be teaching, and the various teaching opportunities I have with Camas Friends, I have been reflecting a lot on what it means for me to be an educator. I want to share some of the key building blocks I am using as I try and build participatory pedagogy. I see three main areas of a participatory pedagogy being: the Quaker tradition, participatory culture, and liberation theology.

All learners are learners within a tradition; apprentices participating in the learning of particular skills, dispositions, vocabulary, practices and styles of thinking and ways of constructing arguments. Therefore, I see myself as an apprentice within the Quaker tradition, seeking to educate other apprentices. Every large-scale tradition has had to develop its own modes of inquiry as it seeks embody its particular arguments in the world. For instance, the Quaker argument that “Christ has come to teach the people himself” becomes for Friends an argument that our ongoing tradition contends for. If Christ has indeed come to teach the people himself then what kind of community must we be? How must we be formed and informed? What are the practices and dispositions a community needs to participate in in order to live into the reality that Christ has come?

Therefore, the Quaker tradition is no different than other traditions in that it is a socially embodied, historically embedded argument about what the good life is. There is a particular style or aesthetic that comes with being a Quaker, certain questions, ways of addressing problems, and practices that form the community given our shared convictions. All learning must be rooted within a larger story and the Quaker tradition is the one that ought to ground a Quaker approach to education. As apprentices within the Quaker tradition our first goal is seeking mastery over the fundamentals, being formed and informed by the community of these convictions, and subsequently learning how to improvise, adapt and “remix” with the tools that one is given from within our particular paradigm.

I believe that one of the most important areas central to apprenticing within the Quaker tradition is participation. Participation is at the very core of Quakerism. That is to say, the absence of sacraments, clergy, creeds and other mediators are not meant to, in my view, communicate an austere spirituality so much as it is meant to remove all obstacles for adherents to participate more fully as co-workers with God in the building up of the beloved community. Within Quakerism there is a priesthood of all believers, meaning that the priesthood is participatory and no longer hierarchical or limited. “Christ has come to teach” is a challenge to Christendom which circumvents participation at every level and instead seeks to position either the church or the state, or an amalgam of both as the mediator between humanity and the Divine.

Consequently, the classroom, congregation, or small group informed by the Quaker tradition must itself be at its core participatory rather than leaning primarily on mediated learning. To enter into Quaker learning is to accept that I must be fully engaged, emotionally invested and fully participate in my own learning. The teacher’s position is to facilitate learning-through-participation. His or her role is to present information and open questions that inspire active processing so that the student can act upon the knowledge rather than simply ingest it. I agree with and am informed by Jane Vella’s dialogue education, which

“views learners as subjects in their own learning and honours [sic] central principles such as mutual respect and open communication” (Vella, 2002).

Participatory education is done through a variety of techniques, including asking open-ended questions, honoring the collective intelligence of the group, creating safe-spaces where exploring and discovery are encouraged, building on collaborative models such as world cafe, and open space technology, and appreciative inquiry and finally building on “connected learning,” which is socially embodied and interest-driven and draws on the power of online tools where necessary (Ito, 2013).

One of the ways I have created socially embodied learning was through “participant observation” we did in the class “Poverty, Empire and the Bible” at Earlham School of Religion (2014). In that class, the students were required to get out into the community and research through interviews, collecting information and experiencing poverty on the ground. Learning was interest-driven in that same class by the way the students formed their own research teams based on their particular questions and skills. As well as by creating “areas of learning” in the syllabus, which allowed students to the freedom to select books based on their interests, while still relating to the course content. There are many ways that interest-driven and participatory learning can take place but it does require work to not rely on the mediated learning model.

Finally, I believe that learning must be oriented towards liberation. Liberation theology is praxis- oriented, democratic and engaged in critiquing powers of oppression. Following thinkers such as bell hooks, Paulo Freire, Leonardo Boff, and Dorothee Soelle, I believe that there must be at the heart of learning a challenge to domination and inequality. Quaker teaching should strive to be many-voiced, amplifying voices that are silenced and non-dominant.* I believe that this aligns well with the convictions of the Friends tradition. The role of engaged pedagogy, as hooks calls it, is to challenge dominate narratives through critical theory, and draw on philosophies and theologies that expose students to perspectives that are justice-oriented, postcolonial, anti-racist, feminist, queer, intersectional in their approach and deal with questions of ableism and ageism. Therefore, a liberative approach to education must be respectful of all students and grounded in the conviction that God who has a preferential option for the poor. In Teaching to Transgress, bell hooks writes,

To educate as the practice of freedom is a way of teaching that anyone can learn. That learning process comes easiest to those of us who teach who also believe that there is an aspect of our vocation that is sacred; who believe that our vocation is not simply to share information but to share in the intellectual and spiritual growth of our students. To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin (hooks, 1994).

All students are children of God, all are equal before God, all deserve the right to a good education. That God has a preferential option for the poor must inform the baseline of our practices of teaching. Teaching is a sacred vocation that invites liberation and transformation for all a part of the participatory learning community. We can incorporate insights from liberation theology into our teaching in many ways: through a commitment to offering a diverse chorus of voices represented in the reading and lectures, inviting students to do “biography as theologies” of leaders whose lives exemplify liberation, sharing the teaching/learning space by inviting others who represent non-dominant positions to come and teach and studying or visiting communities that are themselves working for liberation.

My own understanding of pedagogy is far from developed, it is incomplete, but I do believe that these are important elements. I hope that we can continue to develop a Quaker, participatory pedagogy as we adapt to the needs, and tools of this age.

References:

hooks, bell. Teaching to transgress : education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Ito, Mizuko. 2013. Connected learning: an agenda for research and design. Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Vella, Jane Kathryn. 2002. Learning to listen, learning to teach: the power of dialogue in educating adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Notes:

Mimi Ito uses the term non-dominant “instead of the more common descriptors of minority, diverse, or of color, as non-dominant explicitly calls attention to issues of power and power relations than do traditional terms to describe members of differing cultural groups” (2013, 16).

I have been helped greatly by Dr. Ryan Bolger in thinking through these matters, methods and voices.