The Original Nursery of Truth – Part 1

This is the first of a three-part post on whether or not Quakers can be “Publishers of Truth” today. In this series I want to talk about how I think early Quakers understood what it meant to be “publishers of truth” in earlier years (Part 1), just a couple challenges we face when it comes to a conversation about “truth” as Friends in 2017 (Part 2), and what it might look like for us to have a new the nursery of truth and be “Publishers of the pert near true” today (Part 3).*

The following two parts will be posted in the coming week. Therefore, the links are currently “dead.”

Some of you are already familiar with the idea behind the historical “Nursery of Truth” (and here is a link to a more contemporary version). The idea comes from early Quaker history. As Friends were traveling from Britain to the colonies they often stopped off in Barbados where there was a large amount of Quakers at the time. According to Elbert Russell, it was shortly after 1656 that Barbados became a “major distributing point for most Friends.” As early as 1657 Friends there received a letter from George Fox about his concern for the enslavement of people by those living there.

It became a kind of gateway into the colonies for many traveling Quaker ministers. As missionaries, early friends knew the importances of training and preparation in the truth before heading to America to spread Good News and establish more Quaker meetings. By 1661 George Rofe calls it “the nursery of Truth” (Russell 1979: 39). The nursery of truth was a spiritual nursery where Quaker missionaries and ministers went to grow, be nurtured and pruned.

This word truth comes up in other places as well.

Consider also the very first queries from London Yearly Meeting to be shared with meetings imploring them to gauge the health of their meetings and the Religious Society of Friends:

“How does Truth prosper among you?”

“How many Friends have suffered for Truth in the past year?” (T. Hamm, email correspondence).

Unlike most YMs today, these earlier monthly meetings were expected to respond in written form as a community to how Truth was prospering among them.

And consider the shift that has happened around queries, which tend to function more individualistically today. What was once a plural you, or a “y’all,” which I think I can use now that I live in the South, as in:

“How does Truth proser with y’all?”

Is now often read primarily as a singular you as in,

“How does truth prosper with you, Wess? Or “What is your truth?”

I think that early Friends understood something about truth that we have largely lost under the influence of cultural and philosophical changes that have taken place over the last 100-150 years and that is that truth cannot be understood outside the life of participation in community and a larger-scale tradition. For early Friends, they didn’t just learn truth by osmosis and they certainly didn’t just get to decide for themselves whatever truth was going to be for them – early Quakerism wasn’t a “DIY religion” as some think it is today. To go back to this image of the nursery of truth, I believe that early Friends understood that you have to be apprenticed to the truth and that apprenticeship comes through ongoing participation in a community of practice. Truth can only be understood within the context of an ongoing tradition and the various communities that make it up. I think these may be some of the standards of truth early Friends had that really chafe with our sensibilities today.

But part of what this offered early Friends was the earlier capability to speak with prophetic, Spirit-led clarity and that, in my opinion, is what really energized the movement and got it rolling.

It was also this prophetic clarity that also got early Quakers in so much trouble.

Therefore, another aspect I’d like to consider with you for a moment is not just the purpose of something like a nursery of truth, or the communal aspects of apprenticing people to the truth but also how external parties heard the Quaker messages of truth.

The truth that early Friends operated out of and used was a counter-narrative to the dominant structure of Christendom, and their counterparts did not view it simply as a “different perspective” or an opportunity for dialogue. This counter-narrative was viewed as an untruth, as heresy.

For the early Publishers of Truth there needed to be deep cohesion and communal resonance because the truth they spoke was first received as untruth. It was very much treated as Christian heterodoxy.

Or, as in the words of Anthony De Mello:

The whole world is crazy…The only reason we’re not locked up in an institution is that there are so many of us. So we’re crazy. We’re living on crazy ideas about love, about relationships, about happiness, about joy, about everything. We’re crazy to the point, I’ve come to believe, that if everybody agrees on something, you can be sure it’s wrong. Every new idea, every great idea, when it first began was in a minority of one. That man called Jesus Christ — minority of one. Everybody was saying something different from what he was saying. The Buddha — minority of one. Everybody was saying something different from what he was saying. SLIDE I think it was Bertrand Russell who said, “Every great idea starts out as blasphemy.” That’s well and accurately put.

I think this very much explains some of the experiences of truth and early Friends.

The first renditions of the Quaker movement expanded rapidly but it was not because the way before them was an open-road. At almost every turn the truth they preached was met with opposition. At the heart of the Quaker tradition is a tension with “received truth,” or as we might call in more contemporary circles, “copy-right.” As early Quaker experience suggests: truth often first arrives as untruth. “Impossible!” “Heretics!” “Excommunicate the infidels!” Or a little closer to home: “kick those churches out because they see things differently from us.” “Fire those pastors, staff, faculty, because they are different from us.” These are some of the phrases we hear from the “defenders of copy-right” today, and these are the same kinds of things early Friends heard from “defenders of received truth” back then. This is because prophetic truth, truth that pushes a community towards new life, truth that is counter to the dominant narrative is threatening to the status quo and those in power.

Not only does truth of this kind disrupt the status quo with new life but it can often appear that these purveyors of this new remix are playing fast and loose with sacred doctrine. Consider for example, the response that early Friends received after Margaret Fell’s “Women’s Speaking Justified,” the constant theological debates around whether early Friends were Trinitarian, or their refusal to affirm the church’s creeds. There were well-known, and accepted ways of interpreting texts like 1 Timothy, plenty of received theological arguments about the Trinity, and massive acceptance of the creeds yet, drawing on the same biblical texts, Fell and others came out with very different interpretations. (Taken from my chapter in BeFriending the Truth: Quaker Perspectives).

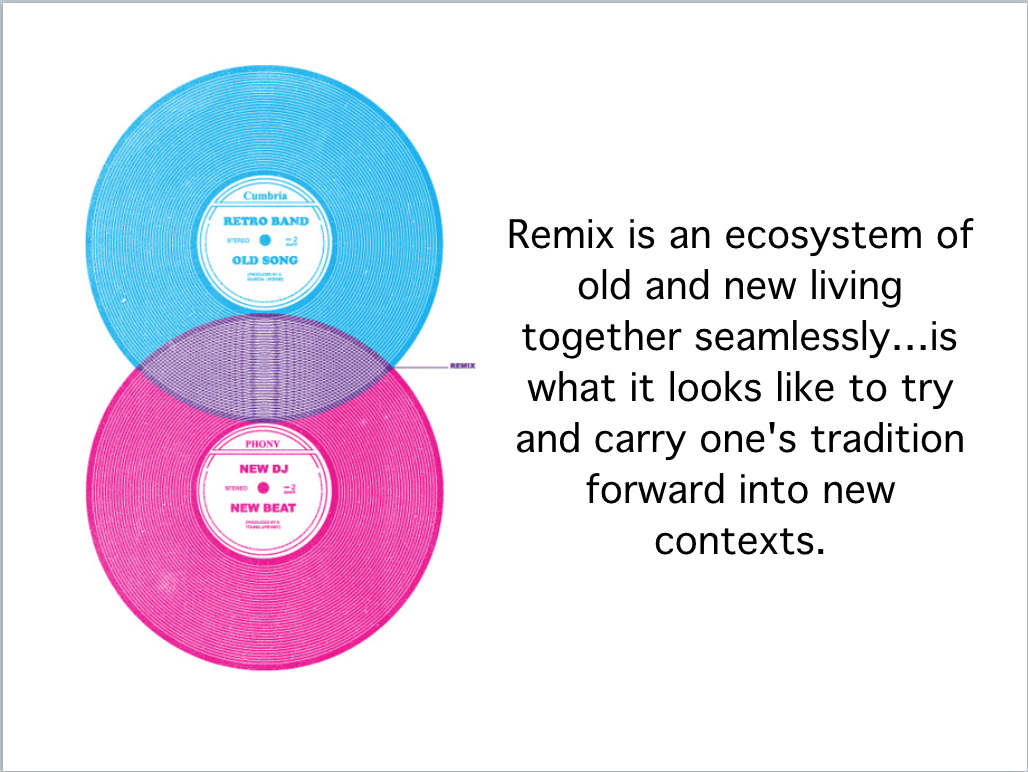

It’s not that they were actually heretics, its that what they were doing could be called in today’s language “remixing” faith or the Christian tradition. A quick definition of remix is that it is:

An ecosystem of old and new living together seamlessly. It is a concrete image of what it looks like to honor a tradition, even while something new is birthed. Remix is what it looks like to try and carry one’s tradition forward into new contexts….(it should also be pointed out that) remixes are often not welcomed, especially by defenders of copy-right.

They get the same kind of reaction that anything perceived as “untruth” ever receives.

So then you have a nursery of truth working to apprentice people to their particular tradition so they can interpret it and reinterpret it wherever they travel and whatever they face, second there was an underlying assumption that to be a Quaker was to be a part of a community of truth and third, there was a liberatory, counter-narrative quality, an initially perceived “untruth” to the prophetic, Spirit-led understanding of truth in the Quaker tradition.

To Be Continued:

1. The Original Nursery of unTruth (or how I think early Quakers understood what it meant to be “publishers of truth” in earlier years) – (Part 1)

2. “Truthiness” In All Its Beauty (or a couple challenges we face when it comes to a conversation about “truth” as Friends in 2017) – Part 2

3. A New Nursery of Truth (or what it might look like for us to have a new the nursery of truth and be “Publishers of the pert near true” today) – Part 3.*

This was a talk given at Quakers United in Publication St. Helena’s Island, South Carolina @ William Penn Center March 2017.